|

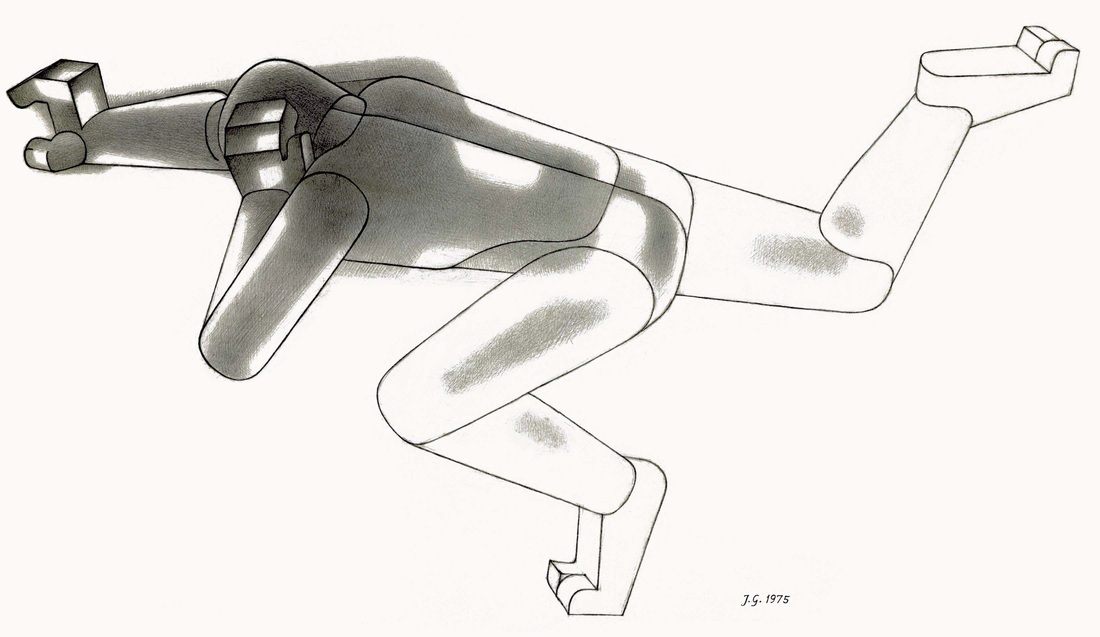

I have spoken to you in these little written compositions of some rather weighty matters. Other inclusions meant to provide a bit of drollery and fun as a respite for both you and me. Here I want to offer you a final picture – not specially related to this or any text – but solely shown to you for your enjoyment. Ahead of me now lie writing tasks which I cannot fit into a tight-spaced deadline plan. I hope you liked my weekly series of reflections, as I surely treasure your attention to it. I am told that volumes are written on humor. Somewhere, decades ago I read, “Incongruity inspires laughter.” We know that not all which exists can be personally meaningful to us. When we encounter something which thus captures us it is because this something engages our minds or touches our hearts. Similarly, to inspire mirth, mere incongruity is not enough. The need is for an unfolding remarkably surpassing daily commonplaces. The lovely smile gracing features in a tranquil, happy moment, as well as festive merriment, are – I think – relatives of humor, for they take us, however briefly, above the mundane dullness of existence. When humor in its biting form is put into an utterance, someone will be someone’s prey whose day no longer will be dull. The benign tease looks upon himself as masterful, but does so peaceably and without inflicting pain. It seems an amiable way to have this fun when one’s victim is only pretended, but not real. Harmless Cyclops Breathing in the Cold A Cyclops is a gigantic, man-devouring mythological being with but a single eye. My Cyclops here is “average-man” – a little plump – bald – middle-aged. But if he resembles closely someone another someone knows, that other someone’s laughter can be more gloating than well-meaning. Let me now recall a masterful political cartoon by MacNelly – masterful because there was no victim: a sturdy housewife, during the Bill Clinton years says to a baffled-looking pollster, “I like the dirt-bag.” The “LIKE”-ing and the presidential “dirt-bag” make odd company. Yet the liking takes out all sting from the unwashed name. So some of us, at least, smiled or even laughed indulgently and fondly. Is not such jesting a deal more loveable than that which gains a triumph through sharpening the claws of ridicule? Summary Mirth includes always the endeavor to master the occasion which arouses it. By that feature humor supplies a true and valuable recourse when hard adversity taxes our courage. And it is a fine conceit indeed to find a way to feel indulgently forgiving toward the President of the United States. Even our gift of receptivity, to happy hours we can regard with smiles, subdues for us the drab, and maybe troubling, every-days. A number of the topics in this series were familiar ground of which I sought to improve my understanding. Though I have had my fun, I have never studied how I had it – never studied humor. So I have to hope that this, my first attempt, has not been too awkward and inept.

Whatever thoughts bounce in and out of our brains or tumble from the lips as speech all belong to their area of interest and purpose of expression. Once my dictionary fell open on the word “atomic,” meaning – not the “super-bomb” – but the least element within each area of enterprise. In visual art the least discernible parts are lines and shapes, and shapes in tones or colors. These can be as small as pen strokes or dots painted with a pointy brush. These “atomics” or “indivisibles” of picture-making are put in place by the artist with deliberation. They are visible to the viewer who may ponder why the artist chose them for their setting in his work. The “indivisibles” are thus precisely determinable and also visibly and clearly separable. Areas of painted colors and lines of varied weight can be more than their material properties. We therefore have here a cube and cone and a dense gathering of furnishings – not as physical facts, but as sights we really see. Whatever appears and unmistakably takes shape inside the picture plane is reality and truth, but such creation is real and true solely within the realm to which it is bound – that of “pictorial art.” Herein we are guided and helpfully instructed in two ways: One is that each path of learning and of progress belongs to its own domain. The second leads us to the just surmise that these truly separate paths will each likely go a rather parallel course. By their differences, and only through those differences, can the diverse disciplines make their indispensable and united contribution to the productivity of the vocations. In a future essay I will try to tell what this can mean to the calling of art.

Dogmatical self-assertion is often met with this riposte: “There is no absolute truth.” Only un-importantly is this correct. However, that reproach against another’s speech is also entirely mistaken. For no one is ever able to even try to pronounce absolutely. All we say is inescapably bound to a subject matter. It cannot be absolute of that subject matter and, so, independent. A runner as fast as lightning cannot exist, but the idea is derived from elements we have experienced. We may therefore picture this or speak about it. Though this runner will never become bodily real, he can become a true creation of metaphor or a magic tale. But no one can express – rightly or mistakenly – anything empty of subject matter. To tell me meaningly, “There is no absolute truth,” is to say that, “A nothing is, in fact, a nothing.”

All we say and all we think – true or false – is bound to its own territory of regard and, in another study, I will pursue that outlook. Monika’s husband is a living “good example.” When once we came to talking, Monika rendered full account of all the helpful chores her Richard happily and always performed for her ease and for her pleasure. So exhaustive was her numeration that I felt need to comment:

Johannes: “This raises an interesting question.” Lucky Lady: “What do I do?” Johannes: “Yes?” Lucky Lady: “I look pretty.” That, I truthfully conceded, the lady did indeed most competently and becomingly. Our friend Natasha industriously nurtures a conceit she is “allergic” to exercise. When I sang the praises to her of the Greek ideal of bodily excellence joined to a clear and incisive mind, the lady told me, “Damn the Greeks!” Now great Ajax and Achilles grimly frown. Almighty Zeus from Mt. Olympus thunders wrathfully. Athena the Grey-Eyed and Bright Apollo are in tears. All Hellas mourns, and even Stony-Hearted ’Hannes grieves. Yet there was a better and more winsome way I could have offered my appeal. Because the Greeks prized Beauty. Our Natasha owns and travels with a store of lovely clothes to all parts of the world. For she is a pretty princess, and I think she knows it. So, let me recommend – with humble duty – exercise as BEAUTY-TREATMENT.

Yr. Obednt. Servant, |

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed