|

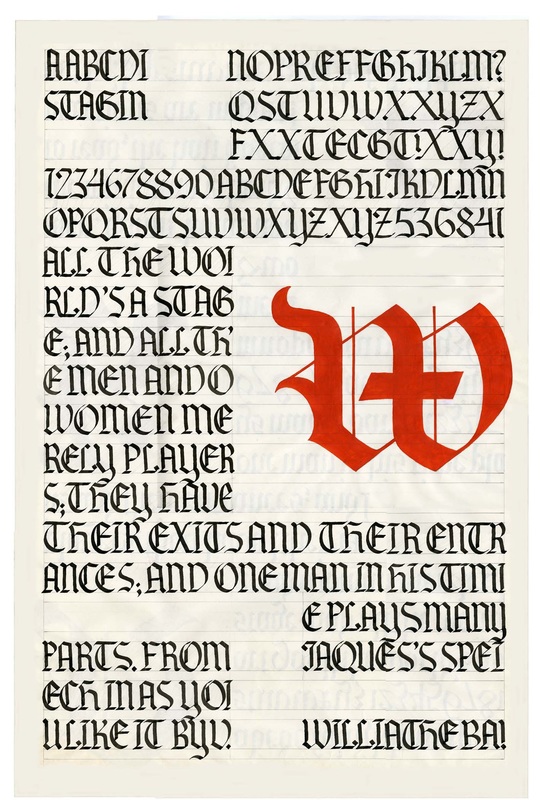

I entered Rhode Island School of Design – RISD, sounded with affection always “RIZ-DY” – in 1951. At that time John Benson, due to failing health, no longer offered lettering instruction. He continued, however, to teach a course scheduled for the entire sophomore class: There has been a vogue of recording “great lectures.” These tended to be only middle-depth in content, rather neatly put together and a little too “dynamically” delivered. John Benson was much different and much better. The course was constructed with exceptional lucid care. Singly, the talks were given with measured calm and very clear exactitude. The pace of progress was always exceedingly reliable, but never hurried. These readings by John Benson were the finest I have ever heard. Swarms of words tend to evade, not master, difficulties. In Benson’s concentrated thinking power, and his patient and incisive discourse, lay our path ahead. The course achieved its excellent success meeting once a week for merely one semester. I never exchanged a word of conversation with this, the most revered of all my teachers – nor did many of my classmates, for we were more than one hundred students in a great lecture hall. A few years later John Benson died, and some years after that I became once more his student. I have two books written by John Benson: one is the translation of the La Operina, Arrighi’s “little work” . . . . . . a great Renaissance cursive writing manual. By Benson’s masterly penmanship the whole is now a most beautiful work of art. The second was The Elements of Lettering, written with Arthur Graham Carey. These two works gave to me a more insightful, and useful, instruction on the lettering art than any others I have tried. In this essay my samples bear doubtless witness to the limitation of my craft, but witness also, I do hope, to the excellence of my preceptor. The monumental stone-carved inscription was John Benson’s especial calling and he was, besides, wonderfully skilled and learned in all parts of the lettering craft. Though knowing much is surely very good, it is measurably better to comprehend deeply and exactly. Owing to that great talent, John Howard Benson – in his task field and at his time – was the best in the world. Dogmatical self-assertion is often met with this riposte: “There is no absolute truth.” Only un-importantly is this correct. However, that reproach against another’s speech is also entirely mistaken. For no one is ever able to even try to pronounce absolutely. All we say is inescapably bound to a subject matter. It cannot be absolute of that subject matter and, so, independent. A runner as fast as lightning cannot exist, but the idea is derived from elements we have experienced. We may therefore picture this or speak about it. Though this runner will never become bodily real, he can become a true creation of metaphor or a magic tale. But no one can express – rightly or mistakenly – anything empty of subject matter. To tell me meaningly, “There is no absolute truth,” is to say that, “A nothing is, in fact, a nothing.”

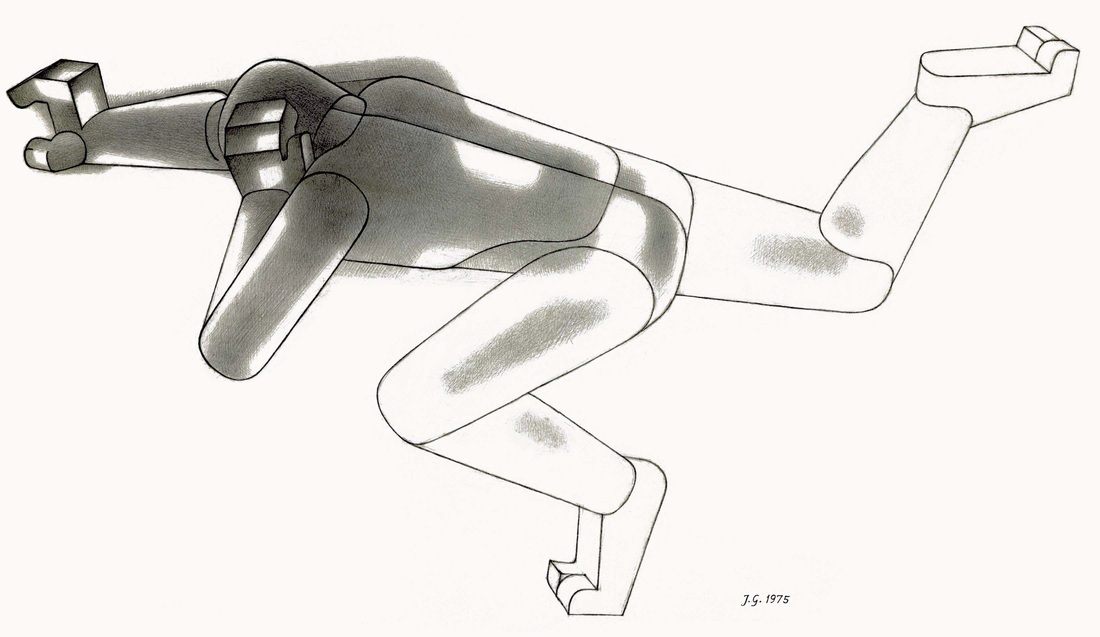

All we say and all we think – true or false – is bound to its own territory of regard and, in another study, I will pursue that outlook. The panorama of the world ranges all about me – I am the unimportant midpoint of the whole. Millennia ago a dwarf, my ancestor, faced four main tasks. 1. For mutual benefit, life in community with others. 2. To gather experience and to learn. 3. Productive creativity – craftsmanship. 4. To render care to personal love. Around this sparse field of action lay – imagined infinite and eternal – a domain of spirit beings. The best known became the Indo-European sky gods and the single deity of revealed religion. From occasions of good will and fellowship in the community and particles of time of happiest love, the dwarf reasoned – not provably but quite logically – a perfected heavenly abode. That land “unknowable” is not the modern dwarf’s chief concern. His once tight field of endeavor has expanded by community growth, research and study, and by manufacture. A widening belt of philosophy, learning, and of know-how now separates me and fellow dwarfs from the transcendent realm. Nature has set us bodily into the center of our world. Through Renaissance and Humanism, Enlightenment and Modernity, we have made that our own resolve.

|

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed