|

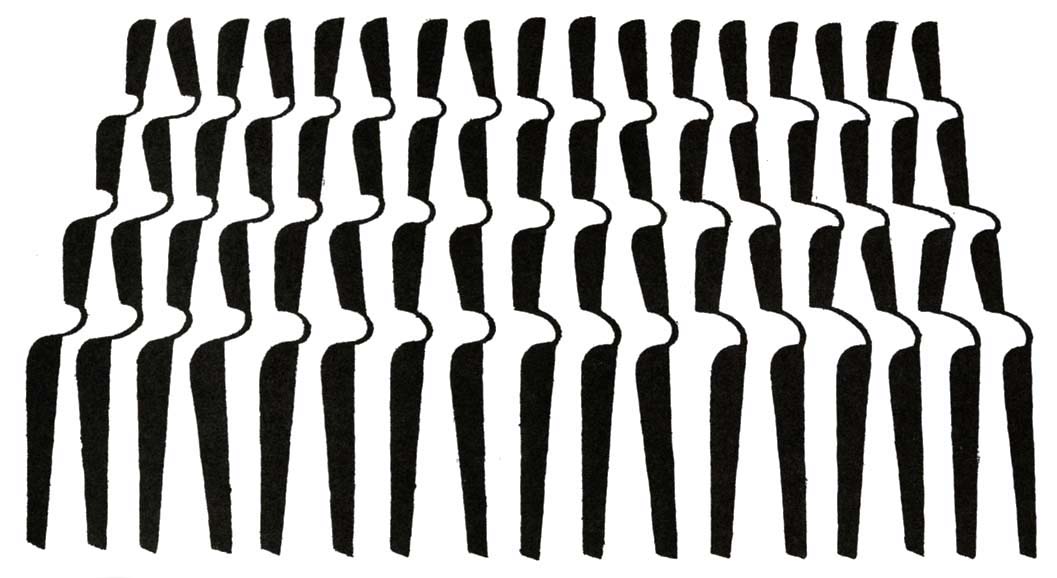

Whatever thoughts bounce in and out of our brains or tumble from the lips as speech all belong to their area of interest and purpose of expression. Once my dictionary fell open on the word “atomic,” meaning – not the “super-bomb” – but the least element within each area of enterprise. In visual art the least discernible parts are lines and shapes, and shapes in tones or colors. These can be as small as pen strokes or dots painted with a pointy brush. These “atomics” or “indivisibles” of picture-making are put in place by the artist with deliberation. They are visible to the viewer who may ponder why the artist chose them for their setting in his work. The “indivisibles” are thus precisely determinable and also visibly and clearly separable. Areas of painted colors and lines of varied weight can be more than their material properties. We therefore have here a cube and cone and a dense gathering of furnishings – not as physical facts, but as sights we really see. Whatever appears and unmistakably takes shape inside the picture plane is reality and truth, but such creation is real and true solely within the realm to which it is bound – that of “pictorial art.” Herein we are guided and helpfully instructed in two ways: One is that each path of learning and of progress belongs to its own domain. The second leads us to the just surmise that these truly separate paths will each likely go a rather parallel course. By their differences, and only through those differences, can the diverse disciplines make their indispensable and united contribution to the productivity of the vocations. In a future essay I will try to tell what this can mean to the calling of art.

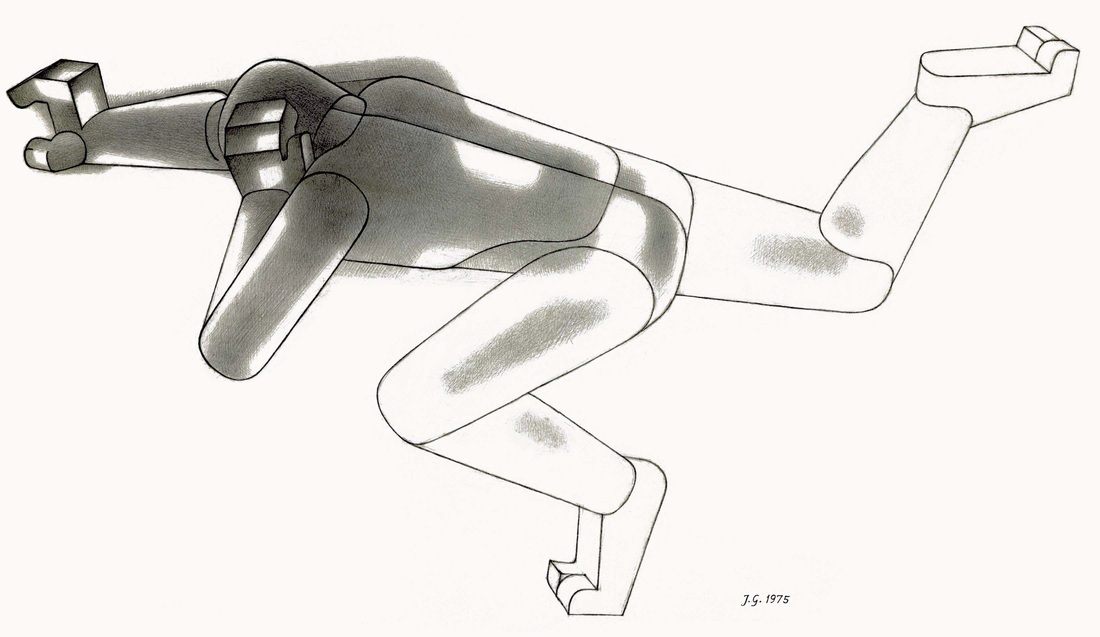

Dogmatical self-assertion is often met with this riposte: “There is no absolute truth.” Only un-importantly is this correct. However, that reproach against another’s speech is also entirely mistaken. For no one is ever able to even try to pronounce absolutely. All we say is inescapably bound to a subject matter. It cannot be absolute of that subject matter and, so, independent. A runner as fast as lightning cannot exist, but the idea is derived from elements we have experienced. We may therefore picture this or speak about it. Though this runner will never become bodily real, he can become a true creation of metaphor or a magic tale. But no one can express – rightly or mistakenly – anything empty of subject matter. To tell me meaningly, “There is no absolute truth,” is to say that, “A nothing is, in fact, a nothing.”

All we say and all we think – true or false – is bound to its own territory of regard and, in another study, I will pursue that outlook. If you read my log you will have met one of my great teachers. Josef Albers is a second. Albers’ color course at Yale was then the sole basic design study really foundational to our work to follow. Colored papers – torn or cut – gave more color learning than paint and brush could have supplied. Colored papers taught also the “simultaneous contrast color-change.” One color may so alter upon different grounds that we give this single color different names – here, once “purple” and, once “ochre.” Albers did not waste his words teaching us not to allow one content or another into the middle of a work, nor on recommending “balance.” What he said was more weighty and a deal more useful. Of a student’s painting he remarked, “I can read this. This is FLOWERS in a bowl.” It was not neglected bitsy pretties in a BOWL. To thus serve the theme and striving of a work teaches how inclusions either damage or support our effort. “I do not believe in self-expression.” Albers’ utterance here causes me to remember another by a friend to a foreign friend, both figures of fiction: “If you can’t be yourself, you’ll have nothing to put in the pot.” We easily miss that the two sayings tell the same meaning from opposite directions of regard.

Albers held that the unimproved, uncorrected self was not the equal of educated and industrious creative individuality. The friend said to the friend, “Let not one of our bad examples tempt you. But bring to us the good you own and join it to the good already here in place.” It is what Albers once said to me of German and American traits – and said it in his native tongue: “Man muss beide im Guten vereinen.” “One must unite the two in that which is good.” |

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed