|

I am told that volumes are written on humor. Somewhere, decades ago I read, “Incongruity inspires laughter.” We know that not all which exists can be personally meaningful to us. When we encounter something which thus captures us it is because this something engages our minds or touches our hearts. Similarly, to inspire mirth, mere incongruity is not enough. The need is for an unfolding remarkably surpassing daily commonplaces. The lovely smile gracing features in a tranquil, happy moment, as well as festive merriment, are – I think – relatives of humor, for they take us, however briefly, above the mundane dullness of existence. When humor in its biting form is put into an utterance, someone will be someone’s prey whose day no longer will be dull. The benign tease looks upon himself as masterful, but does so peaceably and without inflicting pain. It seems an amiable way to have this fun when one’s victim is only pretended, but not real. Harmless Cyclops Breathing in the Cold A Cyclops is a gigantic, man-devouring mythological being with but a single eye. My Cyclops here is “average-man” – a little plump – bald – middle-aged. But if he resembles closely someone another someone knows, that other someone’s laughter can be more gloating than well-meaning. Let me now recall a masterful political cartoon by MacNelly – masterful because there was no victim: a sturdy housewife, during the Bill Clinton years says to a baffled-looking pollster, “I like the dirt-bag.” The “LIKE”-ing and the presidential “dirt-bag” make odd company. Yet the liking takes out all sting from the unwashed name. So some of us, at least, smiled or even laughed indulgently and fondly. Is not such jesting a deal more loveable than that which gains a triumph through sharpening the claws of ridicule? Summary Mirth includes always the endeavor to master the occasion which arouses it. By that feature humor supplies a true and valuable recourse when hard adversity taxes our courage. And it is a fine conceit indeed to find a way to feel indulgently forgiving toward the President of the United States. Even our gift of receptivity, to happy hours we can regard with smiles, subdues for us the drab, and maybe troubling, every-days. A number of the topics in this series were familiar ground of which I sought to improve my understanding. Though I have had my fun, I have never studied how I had it – never studied humor. So I have to hope that this, my first attempt, has not been too awkward and inept.

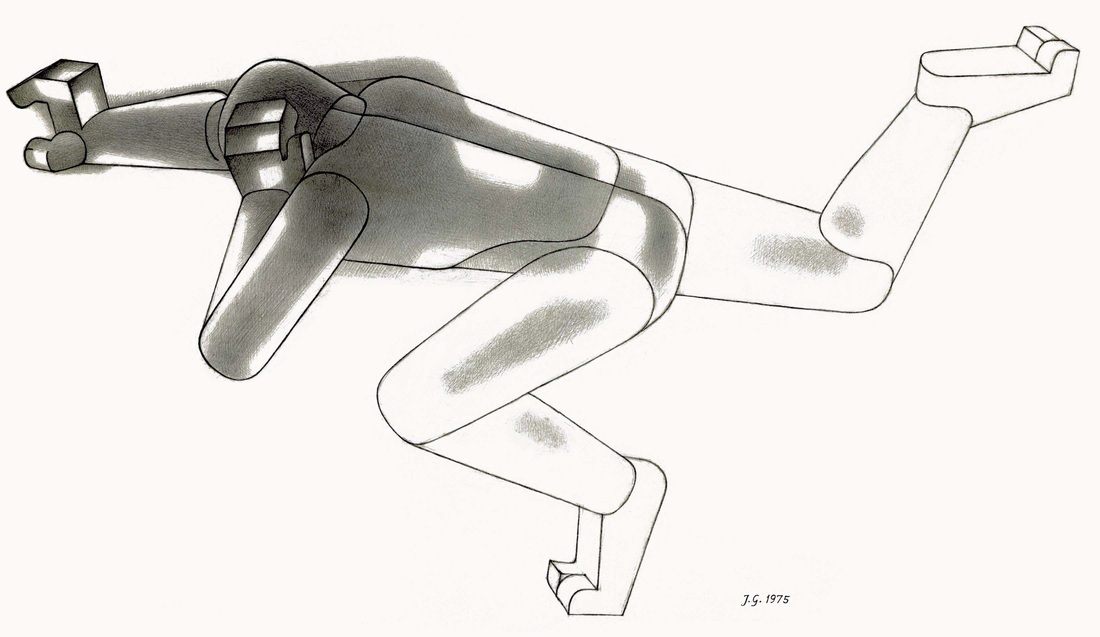

Whatever thoughts bounce in and out of our brains or tumble from the lips as speech all belong to their area of interest and purpose of expression. Once my dictionary fell open on the word “atomic,” meaning – not the “super-bomb” – but the least element within each area of enterprise. In visual art the least discernible parts are lines and shapes, and shapes in tones or colors. These can be as small as pen strokes or dots painted with a pointy brush. These “atomics” or “indivisibles” of picture-making are put in place by the artist with deliberation. They are visible to the viewer who may ponder why the artist chose them for their setting in his work. The “indivisibles” are thus precisely determinable and also visibly and clearly separable. Areas of painted colors and lines of varied weight can be more than their material properties. We therefore have here a cube and cone and a dense gathering of furnishings – not as physical facts, but as sights we really see. Whatever appears and unmistakably takes shape inside the picture plane is reality and truth, but such creation is real and true solely within the realm to which it is bound – that of “pictorial art.” Herein we are guided and helpfully instructed in two ways: One is that each path of learning and of progress belongs to its own domain. The second leads us to the just surmise that these truly separate paths will each likely go a rather parallel course. By their differences, and only through those differences, can the diverse disciplines make their indispensable and united contribution to the productivity of the vocations. In a future essay I will try to tell what this can mean to the calling of art.

Dogmatical self-assertion is often met with this riposte: “There is no absolute truth.” Only un-importantly is this correct. However, that reproach against another’s speech is also entirely mistaken. For no one is ever able to even try to pronounce absolutely. All we say is inescapably bound to a subject matter. It cannot be absolute of that subject matter and, so, independent. A runner as fast as lightning cannot exist, but the idea is derived from elements we have experienced. We may therefore picture this or speak about it. Though this runner will never become bodily real, he can become a true creation of metaphor or a magic tale. But no one can express – rightly or mistakenly – anything empty of subject matter. To tell me meaningly, “There is no absolute truth,” is to say that, “A nothing is, in fact, a nothing.”

All we say and all we think – true or false – is bound to its own territory of regard and, in another study, I will pursue that outlook. The panorama of the world ranges all about me – I am the unimportant midpoint of the whole. Millennia ago a dwarf, my ancestor, faced four main tasks. 1. For mutual benefit, life in community with others. 2. To gather experience and to learn. 3. Productive creativity – craftsmanship. 4. To render care to personal love. Around this sparse field of action lay – imagined infinite and eternal – a domain of spirit beings. The best known became the Indo-European sky gods and the single deity of revealed religion. From occasions of good will and fellowship in the community and particles of time of happiest love, the dwarf reasoned – not provably but quite logically – a perfected heavenly abode. That land “unknowable” is not the modern dwarf’s chief concern. His once tight field of endeavor has expanded by community growth, research and study, and by manufacture. A widening belt of philosophy, learning, and of know-how now separates me and fellow dwarfs from the transcendent realm. Nature has set us bodily into the center of our world. Through Renaissance and Humanism, Enlightenment and Modernity, we have made that our own resolve.

When I say this word I am more often ignorant whereof I speak than comprehending. Talking, for example, of “orthographic projection,” we name a discipline which underlies the classical mechanics of our early industrial action. Our discourse on relationships means not nearly the clear insights and precision that are the implied sense of the descriptive geometric term. If I think of shape and color relations in visual art only as appealing or not appealing, we close down the mind. In an able black and white design, the black renders with care also the white spaces, so that black and white separate and simultaneously unite at their common boundaries. How inventively this is done interests the discerning viewer. We meet with relationships in ubiquitous diversity. The most fateful are those of human people. What we feel and think about, what we speak and do to one another, will either build strongly, or derail, relationships.

Preceding all will be a motivating cause. Out of this completeness of succession – of cause, of feeling, thoughts, and speech and deed, each one is not shown always visibly and truly, nor perhaps, at all. So our demeanor towards one another is a path of pitfalls and of obstacles which frequently we jointly misconstrue. Therefore I do blunder on the path of life I share with others and name those several ignorances my relationships. So I do not much like this word. For it reminds of too much I cannot understand. I make, however, handy use and hide behind “relationships” each time I know too little and want to say it loud. Our hearts are but a dense, polluted pond and hold within all possibilities of Evil and just a little Good. Thus, Frauds and Sinners do not come purely made, so that the names we give them derive from traits we see most often and most clearly. A tattle-tale and backbiter – that is, the Pious Fraud – is upholding virtue at painful cost to others and rewardment to himself. One reward will be most surely a happy triumph of self-righteous Gloating. Our Hypocrites, however, are with us in two species, and not mere one. And that other holds himself to be a Go-Getter and Sterling Fellow. A fluent Liar, his manner is Blunt Honesty, but not his purpose. Those trustable, and also trusting, are his chosen prey. “Caveat Emptor, you damn Fool!” Is profit by Impious Fraud not glorious? Like two species of Hyena are these two – one Spotted, and one Striped. We others are the Ordinary Sinners – we have some Bad in us, and also just a little bit of Good. We believe in Goodness, but do it only on occasion and so, repent of faults, but not too much. “For there is no point in wearing myself out.” Of Saints I cannot tell, as I have known but one. They are our most elusive species, because they try to keep unseen. Comment:

Do you have some favorite "hypocrites" ? A lady poet and a friend of mine opened a series of her verses quoting Nicholas Cage. I do not recall the words verbatim, but the awful meaning was unmistakable and clear: Life is awful; we love all the wrong people; our hearts get broken; then we die. I trust, foolishly perhaps, for myself and for my fellows in a better turn of luck. Our day is dire. Right people love right people wrongly. If your heart be broke, do not presume to die – repair another broken heart imperfectly, because you both are human. In due time, depart this life with Grace. We are right people, you and I, but bunglers in the craftsmanship of love. Dreamily we look for bliss into a distant sky, though our lacks need tending here and not above. We are right people, you and I. Comment:

Do today's problems come more from loving the wrong people or right people wrongly ? In daily use a wooden board or a black line have but the meaning of their thickness and their length, and are only what they can be within these limits. Many boards and many lines will multiply, but cannot better the result. But, when boards are shaped handsomely to make a thing of use, or line joins line to render a design lovely to behold, we are rewarded with a wealth of meaning.

That meaning will be greater than the number of the parts by the exact measure of our labors of the hand and brain. |

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed