|

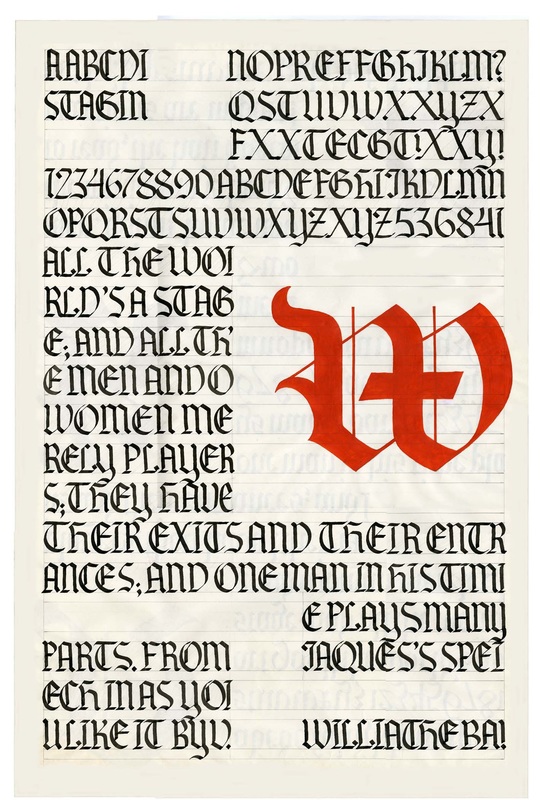

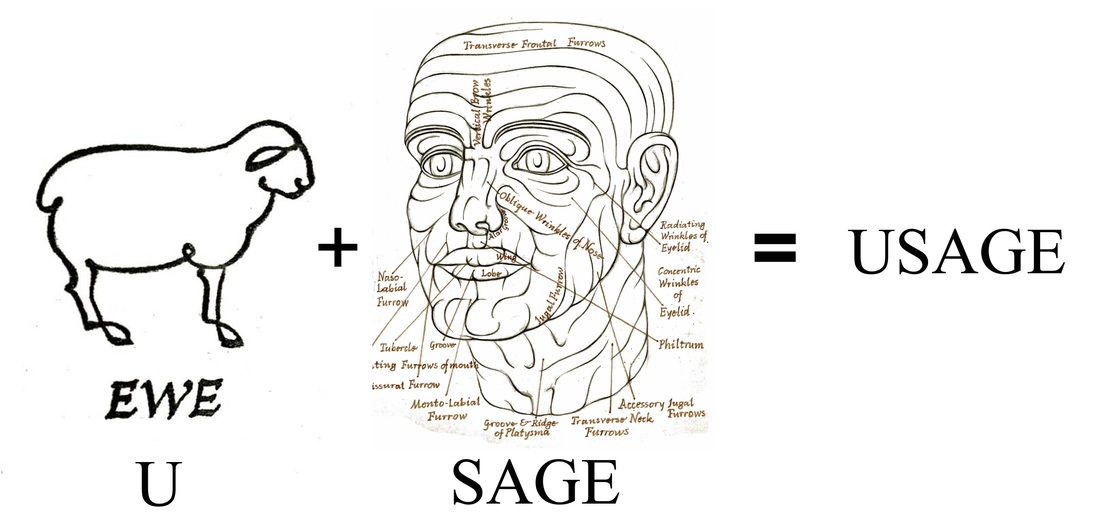

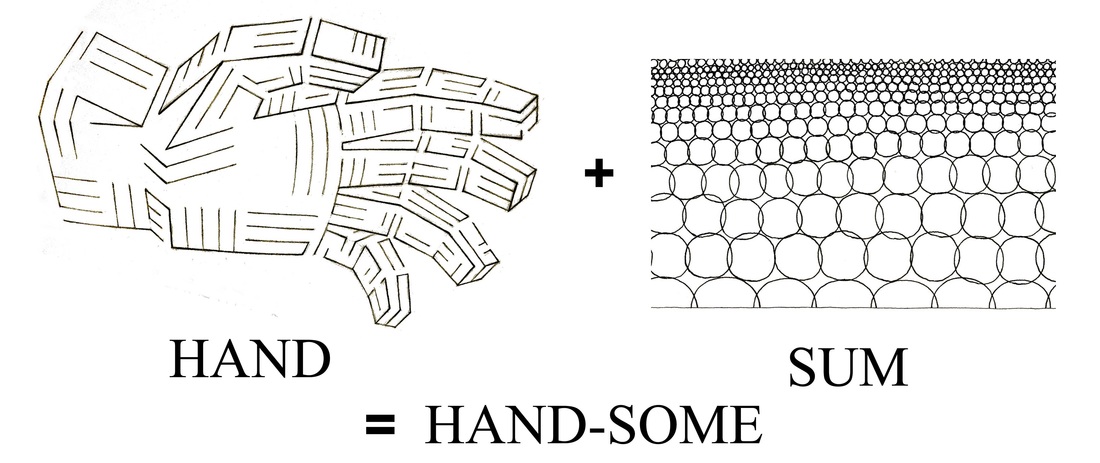

I entered Rhode Island School of Design – RISD, sounded with affection always “RIZ-DY” – in 1951. At that time John Benson, due to failing health, no longer offered lettering instruction. He continued, however, to teach a course scheduled for the entire sophomore class: There has been a vogue of recording “great lectures.” These tended to be only middle-depth in content, rather neatly put together and a little too “dynamically” delivered. John Benson was much different and much better. The course was constructed with exceptional lucid care. Singly, the talks were given with measured calm and very clear exactitude. The pace of progress was always exceedingly reliable, but never hurried. These readings by John Benson were the finest I have ever heard. Swarms of words tend to evade, not master, difficulties. In Benson’s concentrated thinking power, and his patient and incisive discourse, lay our path ahead. The course achieved its excellent success meeting once a week for merely one semester. I never exchanged a word of conversation with this, the most revered of all my teachers – nor did many of my classmates, for we were more than one hundred students in a great lecture hall. A few years later John Benson died, and some years after that I became once more his student. I have two books written by John Benson: one is the translation of the La Operina, Arrighi’s “little work” . . . . . . a great Renaissance cursive writing manual. By Benson’s masterly penmanship the whole is now a most beautiful work of art. The second was The Elements of Lettering, written with Arthur Graham Carey. These two works gave to me a more insightful, and useful, instruction on the lettering art than any others I have tried. In this essay my samples bear doubtless witness to the limitation of my craft, but witness also, I do hope, to the excellence of my preceptor. The monumental stone-carved inscription was John Benson’s especial calling and he was, besides, wonderfully skilled and learned in all parts of the lettering craft. Though knowing much is surely very good, it is measurably better to comprehend deeply and exactly. Owing to that great talent, John Howard Benson – in his task field and at his time – was the best in the world. An art historian once said: “The medieval Church was the poor man’s Bible” – a Bible for unlettered people. In the human past, art told – illustrated, in a way – much of our story. Pictograms can render more coherent meaning, and from Semitic pictographs descends the alphabet we write: Gimel the camel is now “c” and “g” – Yodh the hand – “i” and “j.” Picture-script in English explores how things may express a meaning that is not a thing. The female sheep, a “ewe,” is sound-equal to a spoken “U.” An old man may be a “sage,” a near sound-equal to the end of “u-sage,” a custom. You may regard the circles next the hand below as a sum of silver dollars. Together, “hand” and “sum” say “hand-some,” as in “a handsome lad.” A wig of hair is not sound-equal, but sound-similar to the possessive pronoun “her.” Many and more clever shifts likely conjoined with the pictograms to aid the telling of observations, ponderings, and deeds. To read these meanings by that clumsy multitude of symbols and of signals demanded vast memory and suppleness of mind. Thus the arrival of the phonetic alphabet was a liberation we may justly celebrate. If you speak with clear precision, your words will rightly spell – not in letters – but in sounds. A singular letter-shape for each sound of the spoken word is an ideal very nearly reached by ancient Latin. The accumulated lore of the history of writing was here the teacher who achieved an education excellence by the art of summary. English has strayed way off that perfection, so that often we misspell it. Our 26 characters are not so well on pace to render a letter to each sound of speech as are the Latin 20. Yet our alphabet seems still a miracle to me. For it lets me tell you all I can think and feel, see, and do. Post Script:

I know next to nothing of historical pictography. My considerations here were inspired by opening remarks in a chapter of The Elements of Lettering by John Howard Benson and Arthur Graham Carey. |

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed