|

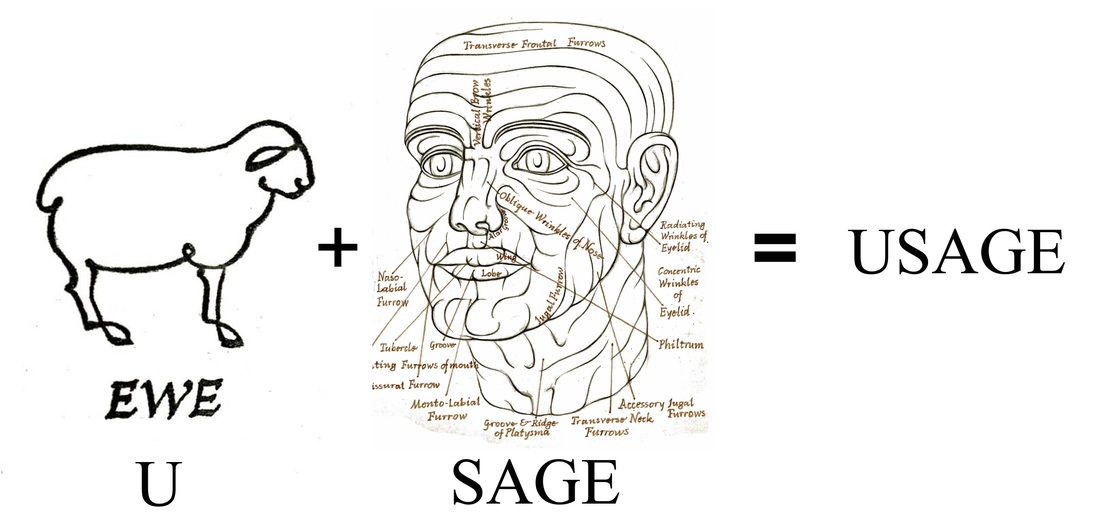

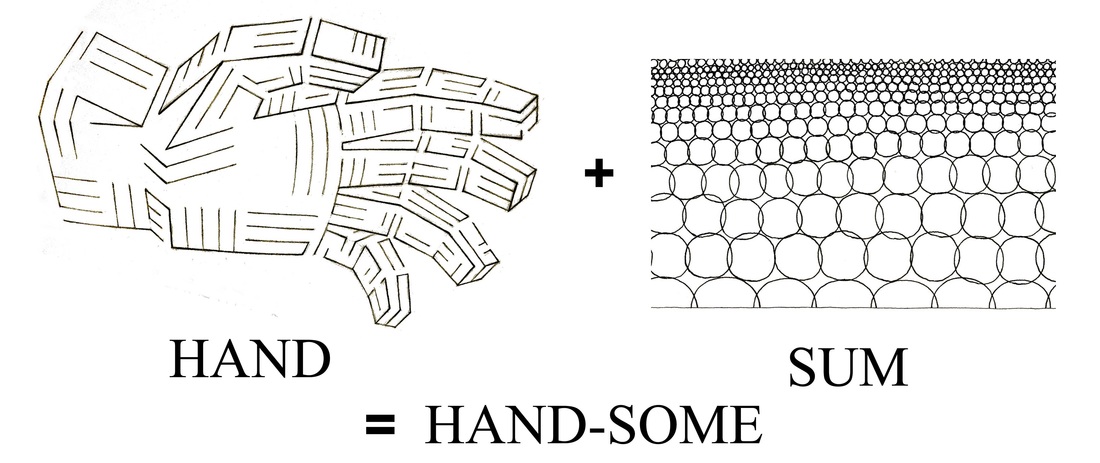

An art historian once said: “The medieval Church was the poor man’s Bible” – a Bible for unlettered people. In the human past, art told – illustrated, in a way – much of our story. Pictograms can render more coherent meaning, and from Semitic pictographs descends the alphabet we write: Gimel the camel is now “c” and “g” – Yodh the hand – “i” and “j.” Picture-script in English explores how things may express a meaning that is not a thing. The female sheep, a “ewe,” is sound-equal to a spoken “U.” An old man may be a “sage,” a near sound-equal to the end of “u-sage,” a custom. You may regard the circles next the hand below as a sum of silver dollars. Together, “hand” and “sum” say “hand-some,” as in “a handsome lad.” A wig of hair is not sound-equal, but sound-similar to the possessive pronoun “her.” Many and more clever shifts likely conjoined with the pictograms to aid the telling of observations, ponderings, and deeds. To read these meanings by that clumsy multitude of symbols and of signals demanded vast memory and suppleness of mind. Thus the arrival of the phonetic alphabet was a liberation we may justly celebrate. If you speak with clear precision, your words will rightly spell – not in letters – but in sounds. A singular letter-shape for each sound of the spoken word is an ideal very nearly reached by ancient Latin. The accumulated lore of the history of writing was here the teacher who achieved an education excellence by the art of summary. English has strayed way off that perfection, so that often we misspell it. Our 26 characters are not so well on pace to render a letter to each sound of speech as are the Latin 20. Yet our alphabet seems still a miracle to me. For it lets me tell you all I can think and feel, see, and do. Post Script:

I know next to nothing of historical pictography. My considerations here were inspired by opening remarks in a chapter of The Elements of Lettering by John Howard Benson and Arthur Graham Carey. |

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed