|

I have long been fond of exercise and, to gain a useful layman’s lore, studied some bone and muscle anatomy and kinesiology. For, real expertise is out of my reach, and “Do this – do that” directives leave much unclear. I therefore sought mainly “first-pace comprehension” and tried to pass it on as “first-pace explaining.” For example, it is easier to give time to warming up when I learn that warm muscles deliver more of their power. In the muscular action of breathing, this brings to us a most welcome “second wind.” The experts know all this and more, yet seldom put any of it into words. My “first-pace explainings” are a help to a fine lady who has begun “working out” with me. Our friend has lauded me most liberally as a patient, gentle, and altogether sterling, ancient pedagogue.

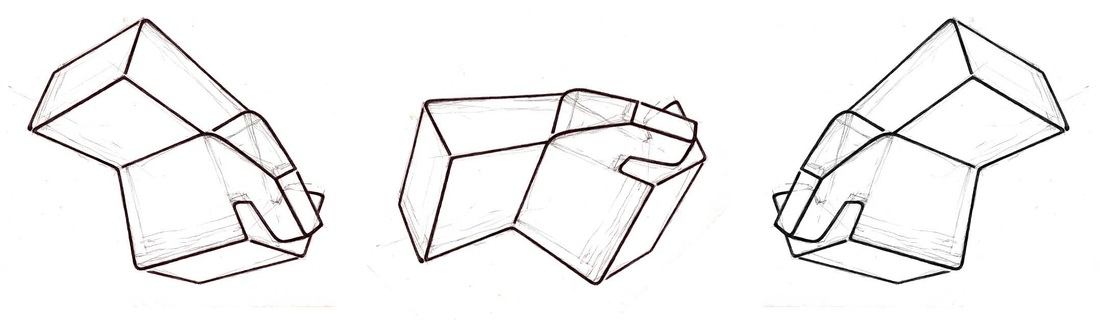

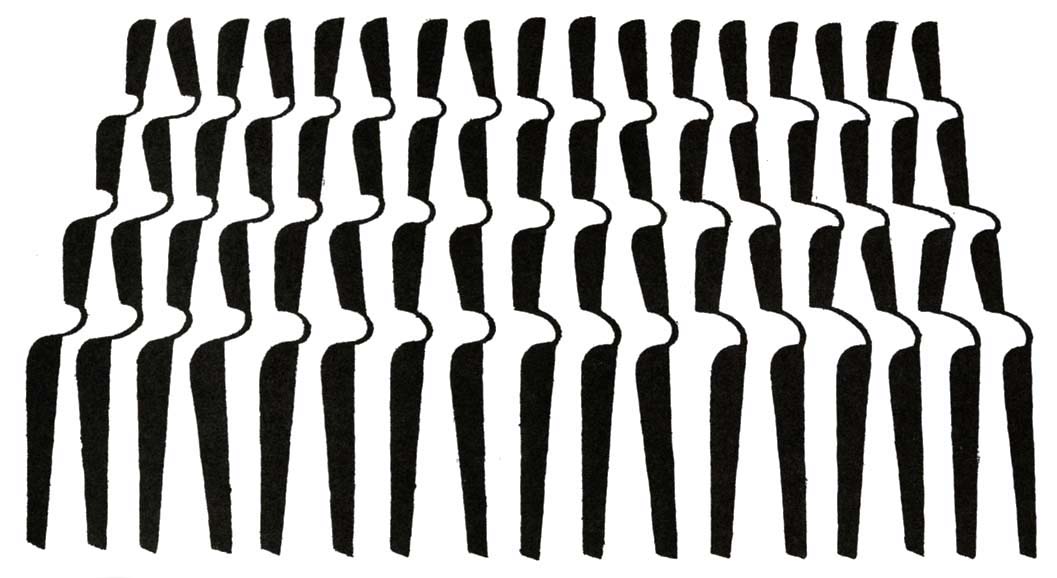

As twice a week is a scanty fitness effort, I inquired: “Do you keep up with your work at home – I mean – when I am not looking?” My nice lady: “No!” And so, with her prettiest mocking smile, “milady” shot me through the heart. When I say this word I am more often ignorant whereof I speak than comprehending. Talking, for example, of “orthographic projection,” we name a discipline which underlies the classical mechanics of our early industrial action. Our discourse on relationships means not nearly the clear insights and precision that are the implied sense of the descriptive geometric term. If I think of shape and color relations in visual art only as appealing or not appealing, we close down the mind. In an able black and white design, the black renders with care also the white spaces, so that black and white separate and simultaneously unite at their common boundaries. How inventively this is done interests the discerning viewer. We meet with relationships in ubiquitous diversity. The most fateful are those of human people. What we feel and think about, what we speak and do to one another, will either build strongly, or derail, relationships.

Preceding all will be a motivating cause. Out of this completeness of succession – of cause, of feeling, thoughts, and speech and deed, each one is not shown always visibly and truly, nor perhaps, at all. So our demeanor towards one another is a path of pitfalls and of obstacles which frequently we jointly misconstrue. Therefore I do blunder on the path of life I share with others and name those several ignorances my relationships. So I do not much like this word. For it reminds of too much I cannot understand. I make, however, handy use and hide behind “relationships” each time I know too little and want to say it loud. Janet and I once were friends with a lovely old lady – she has since passed away – who told us proudly how many beaux paid court to her when she was young. At the time I noted down our exchange together with a summarizing comment.

Johannes: “Did you break their hearts?” Old Lady: “So they claimed.” Johannes: “Did you believe them?” Old Lady: “I believed them.” Johannes: “Did you care?” Old Lady: “No.” Johannes “Tis a hard, hard world in which we live and cruel are the times.” For you and me, my friend, the times and world have not unfolded more accommodating since. If you read my log you will have met one of my great teachers. Josef Albers is a second. Albers’ color course at Yale was then the sole basic design study really foundational to our work to follow. Colored papers – torn or cut – gave more color learning than paint and brush could have supplied. Colored papers taught also the “simultaneous contrast color-change.” One color may so alter upon different grounds that we give this single color different names – here, once “purple” and, once “ochre.” Albers did not waste his words teaching us not to allow one content or another into the middle of a work, nor on recommending “balance.” What he said was more weighty and a deal more useful. Of a student’s painting he remarked, “I can read this. This is FLOWERS in a bowl.” It was not neglected bitsy pretties in a BOWL. To thus serve the theme and striving of a work teaches how inclusions either damage or support our effort. “I do not believe in self-expression.” Albers’ utterance here causes me to remember another by a friend to a foreign friend, both figures of fiction: “If you can’t be yourself, you’ll have nothing to put in the pot.” We easily miss that the two sayings tell the same meaning from opposite directions of regard.

Albers held that the unimproved, uncorrected self was not the equal of educated and industrious creative individuality. The friend said to the friend, “Let not one of our bad examples tempt you. But bring to us the good you own and join it to the good already here in place.” It is what Albers once said to me of German and American traits – and said it in his native tongue: “Man muss beide im Guten vereinen.” “One must unite the two in that which is good.” |

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed