|

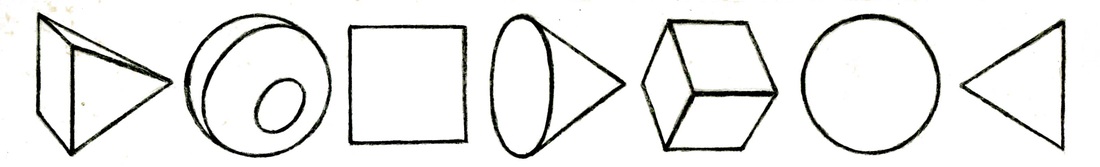

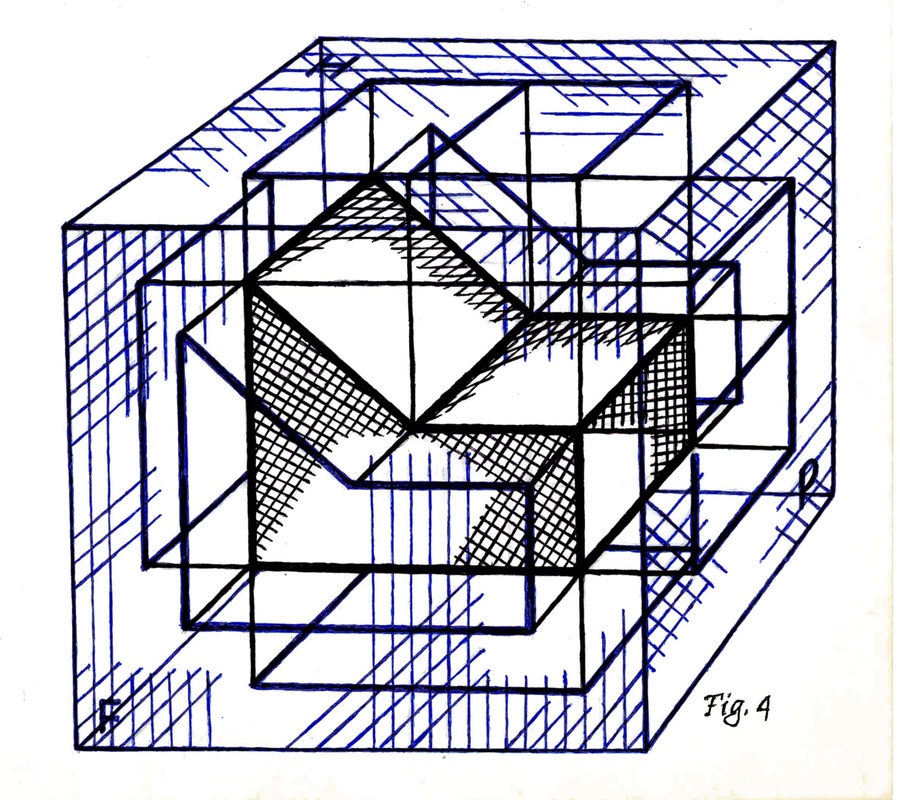

Of the several fine teachers who instructed me as a young man, three were truly great. One, to those who did not know him, Charles Sylvia, the Swimming Coach of Springfield College, will be a surprise. At the start of summer over an extended weekend, Professor Sylvia conducted an aquatics school to sharpen our craft for the summer’s work of teaching aquatic skills to kids. With lucid intellect and with concision – the need to save time obvious – Charles Sylvia complemented and gathered into clear coherence the particles of our comprehension. Sylvia then named that coherence “Basic Knowledge.” Insights and aptitudes acquired singly come together as principles – that is, as rules we use in the work we do. If from such rules is built a useful whole, we will have gained a body of fundamental lore or Basic Knowledge. My sketch below was drawn to explain descriptive geometry to a one-time student. The rendering is a model of Orthographic Projection, the enabling tool of the early industrial age. In level-drafting, the model delivers the three views we mostly want, thus: By their ground plan and elevation renderings, and deep perspective views, we might mistakenly suppose the architects and artists of the Renaissance to have mastered descriptive geometry already – not so. The work was done three hundred years later at the time of Napoleon by Gaspard Monge. Through his edifice of fundamental learning, Gaspard Monge made himself preceptor of the progressive world, and saved that student time – not to squander, but to build and to create. His is a most excellent example of that Basic Knowledge that Professor Sylvia wanted us to learn and put to use. You might comment on a teacher whose "fundamental" teachings went well beyond the announced course subject matter . . . .

There is lofty speech in the colleges and universities on disinterested -- that is, impartial -- pursuit of truth. There is noble sentiment, again, on unfolding students' individuality through centering the action of learning and instruction on their persons. These disparate aims cannot quite join into an accord, but they want to tell the students they are loved. The price tag of a college education may soon reach 200,000 dollars. Can really so much love exist in academia? The colleague long ago whom I most respected judged better: "It is the purpose of an education to save the student time," and "The student should not want to be the center of the educational process, for, if he is, he gets a lousy education." John Spencer Wherever may be found his likes, let me salute them here. Question you might like to comment on : When and why is "student-centered?" appropriate?

In my advertisement redesign, I could not misspell a word. But in the work-a-day . . . . . . errors are the Rule of our road.

I deplore my -- and others' -- missteps, our slipshod haste and corner-cutting self-accommodation. Some follies I have ventured need forgetting . . . . There are failures that ignite the brain with comprehension. Those dead-endings become roadside lanterns shining very piecemeal upon the path ahead. Such errors have a value that deserves reporting to save a later worker needless wanderings and time. A century ago, aircraft seemed the miracle of their time, yet were full of aeronautical mistakes. Thus -- we fly today frequently and safely and at speed. Schoolboy mathematics can be a perfection, if the schoolboy knows the answers. Beyond the lecture hall and classroom, we build short-falls upon a fundament and ground plan of successive short-falls. This is never easy going. So, give yourself, and give to me, a liberty to celebrate each time we gain a pace or two ahead. Feeling as EMOTION

Live beings emote because they will to live. That is, they own a drive to outward action whose always purpose is to repair a deficit: when we are hungry we seek food, in peril -- safety. Along the path of labor on his pictures, an Artist learns the burden of emotion. For a work still incomplete is a wish not yet come true -- a short-fall to be mended. . . . and as RECEIVING Speaking of happiness emotes a need to reach a hearer -- perhaps a sharer. Happiness itself, however, enters the accepting heart as a near-celestial blessing and perfection of fulfillment. Emoting nothing, we partake wholly of a most liberal receiving. When art works render depths of grief and dire misadventure, they will not make happy. Yet, if they engage all our attention and whole participation, they afford fulfillment. We are not strong enough to endure for long this all-demanding state of being. The spirit wanders. Our attention must soon divide, and the lacks of our world require care. |

Johannes

|

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Speaks |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed