|

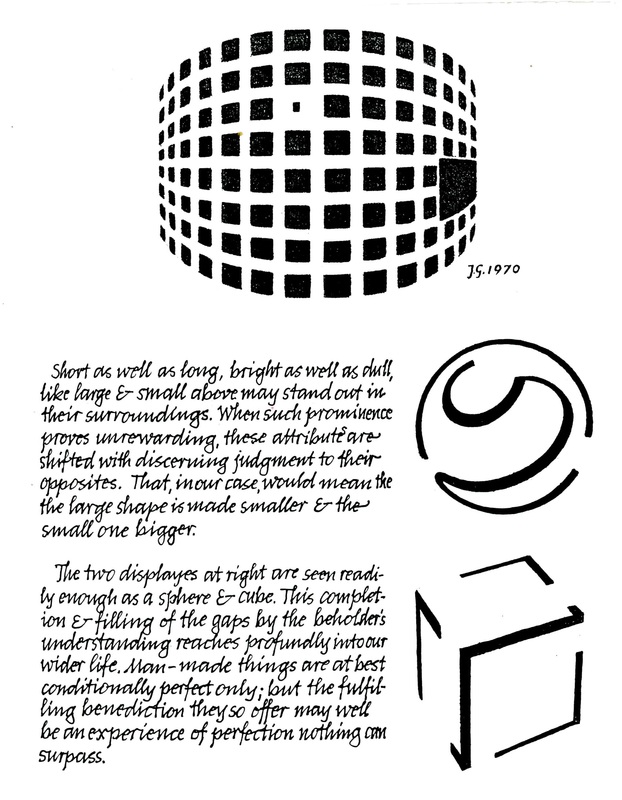

The FINAL week -- with summary conclusions for "What is a beautiful thing?" and "Why pursue beauty?" and the meaning of true fulfillment for our leisure time. F. The Definition – What is a Beautiful Thing? Just as a thing is interesting when it engages the participation of the intellect, so is beauty its ability to engage us through the senses which, in our present line of interest, is the sense of sight. If we have reached agreement on my live demonstrations, two things will have been made clear.

display. It is the ability to look at ourselves while looking at a thing. G. The Purpose – Why Do We Pursue It? If we ask what makes a beautiful thing desirable to have, we get invariably the reply: “It pleases.” So it often does, but decidedly not always:

Literature, of all the arts, uses the comprehending intellect as if it were one of our senses. For, the reading eye alone would see page by weary page a single basic pattern endlessly repeated. But form and composition speak at first to the brain itself as if it were purely an organ of reception – a retina and eardrum of the mind. What unfolds in all my three examples are terrifying tragedies. To be gratified or well-pleased with them would be indeed satanic pleasure – a diabolical amusement. But, even while the heart is saddened, these works can so utterly engage all our mind and feeling that no foreign desires are able to intrude, and no distractions tarnish, the experience. Thus we learn through them a perfection of fulfillment.

The Purpose – Why Pursue Beauty? (cont’d)

2. But to love and learn about the Arts we have to measure up to them. We have the right to assess any work against the artist’s claim – his promise, if you will – that he is showing it to us because it will be a first rate thing to see. Yet, as viewers we must have good will, seek to un-learn our prejudices, and shed the common failing of ill-tempered and pedantic carping. For these will surely shut the doors on art. Besides good will, and by the instrument and reason of good will, we have to learn to open our eyes and to develop a clear mind, to be – to the best of our ability – a Noble Viewer for the artist’s work.

The Sciences – and here we must include Philosophy among them – are also fulfilling and enriching. But the Fine Arts and the Sciences cannot take one another’s place.

The Arts, however, can transport us to another world where our daily troubles matter little, and where we are refreshed as if we went on a vacation.

but because it simultaneously enriches and fulfills and restores our weary spirit, in a compact – one almost wants to say “efficient” – form that nothing else can quite achieve. 4. Finally, works of art can give to us this true refreshment and unburdening from our common cares in ways no artifact can altogether equal. H. A Change of Pace Rather than Escape

weaken him in the execution of his tasks. We assume therefore that ugly surroundings damage man’s ability to perform his proper work in life. Yet the unimaginable hell of a world entirely devoid of art – despite our inner city slums – still remains, I hope, mostly outside of human ken. But we are not prevented by our dependency on art from also wanting the truth of science and the reality in which it operates. We are not put to flight by reality. 2. The escapes of mindless thrills and pleasures cannot provide this change of pace we need for our restoration. For, largely disengaged intellects and sensibilities mean a relaxation of no pace at all.The mind-deadening effects of numerous television offerings – that is, the resulting sluggishness toward mental action – show that downward self-fulfillments as a class, far from giving us refreshment, put us beyond the reach of any restoration. 3. But the Arts demand of us a diligence and an attention that will bring us true enrichment instead of a mere land of dreams. For they alter solely the use we make of our faculties, and thus sharpen them into alertness, instead of rendering them numb. Leisure time is time which truly belongs to ourselves, and we should get from it all the benefits we may. The Arts are more suitable than almost any other instrument for gaining such a purpose. Johannes H. von Gumppenberg Lancaster, PA October 24, 1995

0 Comments

During the past several weeks, Johannes gave detailed descriptions of Basic Design courses. Here, after some final thoughts, the essay returns to philosophical topics - aesthetics. (NINTH of eleven sections) I. Basic Design within the Foundation Program Within the Foundation Program the two semesters of Basic Design are by themselves a compact summary of an artist’s purely visual work of form and color, as opposed to figure or landscape drawing. Apart from the special mission of three-dimensional composing, the Surface Designs divide the language of their visual domains very carefully into the parts of art and gradually join them toward a plane of competence where the student will be no longer a beginner. To summarize the tasks of a two-semester Basic Design course: Basic Design I:

J. Historical Study 1. Artists need a grounding in Art History to see how cultural excellence – due to causes that fundamentally can never vary – appears in every period and all kinds of places.

2. Besides needing the History of Art to train their eyes at discerning other workers’ best creations – regardless of how unfamiliar may be the face they wear – artists want this study, as every man must want the history of his own kind, for the assuring companionship it offers.

There is no time for me to treat in our framework any useful portion of the History of Art. But we can deal here with the major steps in the development of Western Writing, whose dual heights of excellence must substitute for the miraculous abundance of the history of art which, alas, at present, poses an unwieldy horn of plenty. 1. Our Alphabet is the lineal descendant of Phoenician characters, which are thought to go back to Egyptian pictographs, or to have been independently contrived in Phoenicia. Aleph the bull became Alpha and “A,” Beth – the house, Beta and “B,” Gimel – the camel, Gamma and “G,” so that our word “Alphabet” itself is of this North Semitic origin. 2. Pictographs are unevenly exact sound-alikes. A picture of a deer could do duty for addressing some we are fond of, as in “my dear” and, less precisely, a “gull” as in seagull might mean a “girl.” When Aleph, Beth and Gimel turned into Hellenic Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, their names became mere pronunciation keys for the initial sound and the Phoenician meanings disappeared. Along the way the pictographs grew simpler and more geometric in design, and so became true letters. 3. Around 200 BC, ill-crafted linear letter skeletons, more of a Latin than of Greek appearance, assumed truly geometric character in the centered horizontal bar of “A” and the semi-circles of “C, D, S and R.” The geometric character since then has been preserved, but was modified correctively to give aesthetic satisfaction. These changes produced in A.D. 100 the Monumental Stone-Carved Roman Capital, with the thicks and thins, as well as serifs of our present day. 4. The monumental Roman Capital is the first of two lettering masterpieces we have in Western Europe.

5. I am indebted here a second time to John Howard Benson – who was the greatest writing master this country ever had – for my brief history of lettering. In his understanding, Chancery Cursive is the finest possible compromise between the needs of the reading eye and our rapidly writing hand. 6. Should we venture, perhaps rashly, to design an alphabet of our own, we must consider this historic line in order to remain inside the bounds of legibility.

If we paint and draw still lifes, landscapes, or the human face and figure and think that lettering can teach us nothing, then we are not true students of the arts we practice. For an excellence a little off-side of our personal striving allows us to dismiss for a while our own designs and can refresh our fatigued and clouded minds, thus crystallizing our judgment and brightening our vision. To perceive in other disciplines how he may improve within his own, characterizes the ardent student and true learner. III The Likeness of a Beautiful Thing A. Two Questions You owe this portion of the series to a one-time student who wrote me letters with questions about art to which I replied in essay form. One exchange dealt with the theme: “Why do we make art?” Two questions reside within the one:

Both of these are philosophical concerns, and a philosophic bent of mind will help us to consider them. But philosophic learning all alone cannot succeed, because the task requires also the experience of a working artist. Because of this, my discourse will not be exclusively a set of philosophical reflections, nor center only on artistic action. But, giving both their due, we may achieve right understanding and thus reveal most clearly what an artist will find proper and worthwhile to do. B. The Meaning of the Term “Art” Art is a strange word, not for what it means, but what it fails to mean.

In the great puzzles of existence, groping in the dark may be common in Philosophy. But otherwise, so much groping in the dark is not altogether usual, because language strives for our understanding, and not to deepen the confusion. For example, “lawnmower” and “dishwasher” proclaim at once what these appliances are and the service they deliver. My task is to make as precisely clear what art is and it does for us, as the names lawnmower and dishwasher make clear the function of those objects. To make as clear, however, does not mean to state as briefly. On the contrary, I must, to some degree, become substantially long-winded. C. The Claim Implied through Showing Art

rich reward.

Comment:

Has some other discipline offered you insight into the practice or appreciation of visual art? We begin this series with the early essay which gives its name to this column - written in 1959. (Final of six sections) Summation – The Principle of Meaning

At last, I hope I have been able to clarify some aspects of the principle of meaning. I have presented my theme by discussing meaning as the content of all identities. I have done this without insistence, beyond illustrative example, upon a specified meaning belonging to a specific thought or object. And I have collected the being of all, however variedly distinguished entities, under one name – meaning – and tried to show what principle rules the nature of all things under this generalization. Here at the end I wish to summarize the conclusions that perhaps have been reached. Meaning is the content of being. This content, that has been named “meaning in the absolute,” includes the potential power to contribute its meaning to the content of another being under the term “meaning in the relative,” for which meaning in the absolute is the presupposed condition. When man has reached the limit of knowledge accessible to his mind, he can yet relate to the remaining unfathomable existence or void by faith in an omnipotent, infinitely wise and just deity. I believe that, even without a living God, the act of faith would be valid and meaningful – for faith is included in the endowment of our identity. And because we desire to know ourselves, we must experience our own power of faith, not necessarily because in faith we believe correctly, but because perceiving ourselves in the act of faith enlarges our self-knowledge. To know himself and the role of his entire being, man must use his power to relate. This is absolutely his sovereign possession and, by employing it, he gives evidence of himself to himself. God, however, all-knowing, needs no such demonstration of his creator identity. His self-knowledge of it would be complete without the test of creation. In the end I have written this paper as a personal guide in my own endeavor to distinguish and separate meaning from non-meaning, sense from non-sense. The meaning contained in our being, and in other existences, becomes perceivable to us mainly in the relation of ourselves to the environment. In such a manner, the search in these pages may, over the years in a small measure, help to reveal the content of my own identity. This seeking, rewarded at best with only partial finding, is the task of our lives. We are committed to it because insight into the nature of our identity from within is the required condition for insightfully relating to the world without. By so seeking we acknowledge ourselves, in the realization that being is the vessel which holds all the meaning we can ever hope to find. We begin this series with the early essay which gives its name to this column - written in 1959. (First of six sections) The Need for Meaning In the course of a daily increasing span of life, events and concepts accumulate to reach gradually a degree of confused complication that becomes unmanageable in its ever waxing quantity. The will to search for a basic principle which endows with meaning the enterprise of life, and all that it entails on the human scale, is at once natural and inevitable. These pages intend to examine the condition of meaning, in the hope of excavating a foundation upon which we may think and act – not perhaps with certainty but with, however, a resolution wholly unlike the uncommitted indecision that characterizes the waste of futility. From the recognition that we are able to discern meaning in nothing which does not in some manner take effect upon us, we obtain a first indication of a feasible direction in which we may pursue our search. Thus we have some reason to at least suspect that the particular way in which one thing makes its impact upon another contains what meaning is to be found, not in either one, but in the relation of each to the other. Consequently, we quite reasonably arrive at units of meaning of variable complexity, which must seek escape from futility in borrowing a reason for their existence by relating to yet further units. In this process of continuing and enlarging relationships, the point is ultimately reached where this interpenetration of related meanings is contained in one vast system which comprises all available associations and which, now in its turn, must find a source which will contribute meaning. Such a contribution can no longer be contained within the natural world and would have to be the prerogative of an infinite, almighty, and divine existence. Meaning, however, on the level of divinity, is totally incomprehensible to the mind of man. And if this investigation is to continue at all, I must assume that meaning in the lives of human beings takes its place in the natural world and may be understood -- within this deliberate reduction to the measure of man – by the natural powers at our disposal. If that assumption be a violation of the essential character of meaning, and if I possibly reduce something to my own scale which, in fact, bears no reduction at all, I would yet be forced to take upon myself the risk of committing such an error. For the realization that, without so risking, I should be deprived of my theme altogether, appears to justify that I confine the problem to humanly manageable proportions, because it does exist validly and perceivably in the earthbound environment of humanity. Relative or Absolute? As long as we look upon the substance of meaning as the result of the associations among all things, we find that these relationships will outdistance us to the point where human intelligence can simply not follow. It is hence necessary to at least make the attempt to discover meaning not in the indebtedness of one thing to the other, but in a more sovereign sense which I should like to name “meaning in the absolute.” – The expression “absolute” here is not an identification of divinity. Its intended interpretation is antonymous to the word “relative,” and therefore close to the Latin root “absolutus.” For, in spite of the fact that we have observed that experience with meaning tends to be limited to the effects that invade our lives from the outside, or more briefly, tends to be “meaning in the relative,” each of these sources of relating influences does have a character and quality particularly its own. Quite independent from any ties with its partner in relative meaning, it does have identity, and we shall have to ascertain whether this contains such significance in its own right that we obtain indeed meaning in an absolute sense. |

A Blog containing longer text selections from essays by Johannes, on art, philosophy, religion and the humanities, written during the course of a lifetime. Artists are not art historians. People who write are not all learned scholars. This can lead to “repeat originality” on most rare occasions. When we briefly share a pathway of inquiry with others, we sometimes also must share the same results.

Categories

All

Archives |

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Writes |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed