|

In the early 1990s this was given first as a speech to a class at the Lancaster County Art Association, and in briefer form afterwards on a couple of other occasions. Some of the illustrations come from the text, others from references to physical works that Johannes brought with him, and one from live demonstration. (3rd of eleven sections) II The Transmission of Knowledge A. Dexterity Training Today objects of utility are products of industrial virtuosity and “know-how,” and the machines that shape them are the vastly powerful offspring of the classical tools designed for manual use. The computer may permit a parallel industrial development also in the Fine Arts toward which, at present, there is both skepticism and enthusiasm. We must admire the sheer technical magnificence that the computer has made so readily available. But the seeing eye is subtler than we easily observe and may find eventually something bleak and arid in endless repetitions of computer “fireworks.” It would be a sad result, if all the love and adulation lavished today on the computer, brought to us tomorrow a nostalgia movement for the second time around, because our prevailing culture of that day will be too sterile and too feeble to nurture our souls.

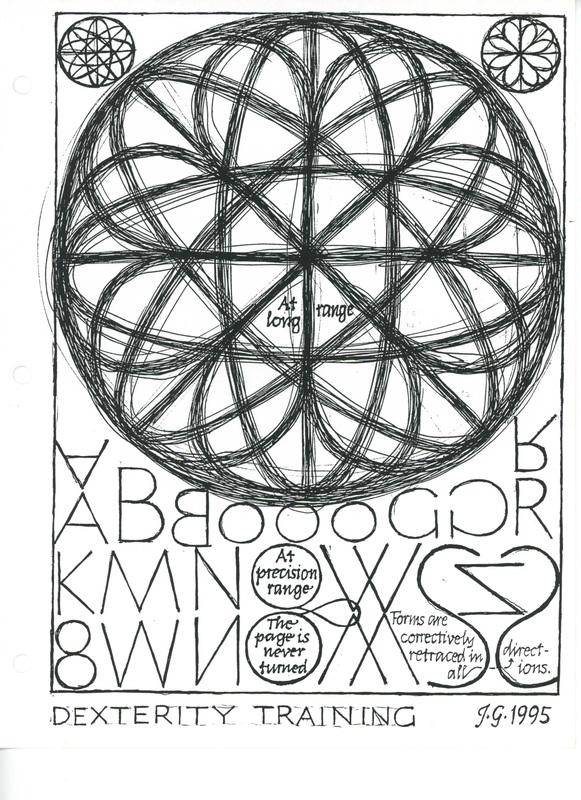

2. Skill Training in Calligraphy and Drawing: I have known only a single Drawing Course prescribing exercises, in the form of drills, for manual control. Instead, Calligraphy has generally taken up that task to much good purpose, so that, even in my drawing courses, I have included letter forms for dexterity instruction. Dexterity improves to varying degree with any art work we perform – but only over time, so that, in the present series of four speeches, I cannot help you to become more skillful. But I may attempt to add a little to what we understand. B. Intellect and Will Will, Intellect and Intuition are used as words so confidently that it is easy to be unaware how little we were ever taught about them. Though the will cannot determine what the knowledge of a subject is, this knowledge cannot constitute itself without the energy of the will.

2. The Will: Not all feelings are emotional. For we can receive them in happy timespans of fulfillment while emoting nothing.

us how frivolously one may employ both intellect and will. The emoting Will can enslave and put the Intellect to work for any cause. 3. Education: In youth our unattached emotional energy surges in every direction. And through education – not by the schools alone, but in the sense of an ancient wisdom out of Africa that it takes an entire village (a whole society) to raise a child – we must hope to reach that vast reservoir and powerful potential.

one of requirements – though we meet them badly – and not just personal bent and impulse. Eventually, self-expenditure can help youth to cherish the good products of their labor more than any ready pleasures falling unearned into their empty lives, and to cherish also in a little way themselves as people who have worked faithfully to learn to behave properly and labor thoroughly and well. And so the personality begins to grow into an enduring likeness of the way we live and work.

C. The Three Ways of Seeing as Three Ways of Learning The Three Ways of Seeing would be: Naturalistic Seeing – through Observation; Derivative Seeing – from Experience; and Original Seeing – as a Creative Vision. This last inclusion is owed to John Howard Benson’s course. When we call these three divisions the Three Ways of Learning, some of them may gain a little ground.

2. Derivative Learning is a discipline of Prudence, or Right Doing, as well as of Right Knowing, gained from our teachers rather than from Nature. It is the Learning transmitted through an education based on past experience, and its value is two-fold:

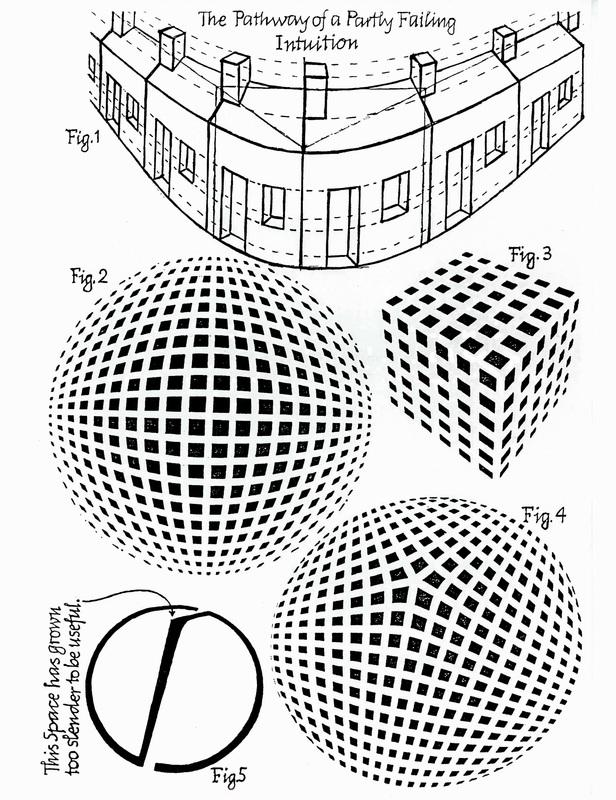

the most up-to-date, at the time of teaching, is confirmed. So, if he masters it and learns to work with it, the student cannot really fail. 3. Original Learning: To profit as abundantly as possible from listening to others, we must listen also to the voice of our personal understanding – that is, to ourselves. A self-created pattern of sensible, experimental forecasts must now provide the guidance to a deeper understanding and a more useful, nobler product. That achievement is the work of intuition that I must now describe in some detail. Useful intuition comes mostly to the well-prepared. D. The Pathway of a Partly Failing Intuition

2. An intuition is easily mistaken for a feeling, because the well-familiar information from which it is descended is taken much for granted and hence no longer paid attention – and also because hope, even anticipating joy, attend promising intuitive perceptions. An anticipation – no longer perceived against the background of its origins, and attended by strong feeling – will easily itself appear as a feeling. But we can no longer so mistake intuition if we keep in our sight the preparatory knowledge which brought the intuition within the range of our speculations.

3. Intuition is precognitive (foreknowing) in its character, and does its work by leading us to knowledge – that is, to full cognition. Given their rational foundation, its forecasts have to be of intellectual substance – not as a solid certainty – but as an intellectual probe. Thus I rely upon my intuitions all the time. For without its capabilities, there are no advances. But an intuition can only serve us well if we treat with skepticism every result it urges and then express our distrust by a thorough work of testing. This is truly most important – that you must distrust your intuitions in order to obtain from them all the benefit they have to give. 4. Were I to be your teacher, perhaps daily over many years, I could help you to improve your skill and show you how you might proceed, with prudent discipline, to achieve the results for which my teaching aims. But I could do no more – and it is a most uncertain game – than hope to stimulate your intuition. And you might not like me very much for trying. For Stimulus is Latin for a cattle-prod, and who could welcome the sort of treatment such a tool implies? Important intuitions must instead result always from lighting one’s own fires. But useful knowledge – as we have clearly seen – can provide the kindling spark. And I may share with you, perhaps, some useful knowledge even in these few short hours we can have together. Comment:

Have you ever encountered a course like The Philosophy of Design taught in the 1950s by John Howard Benson?

0 Comments

In the early 1990s this was given first as a speech to a class at the Lancaster County Art Association, and in briefer form afterwards on a couple of other occasions. Some of the illustrations come from the text, others from references to physical works that Johannes brought with him, and one from live demonstration. (FIRST of eleven sections) I The Artifact and the Art Object A. Rules for Right Making in Utility and Art In past times distinctions were drawn between products of the Fine Arts and humble Objects of Utility, adding to the latter ever the inferior rank. Much thinking in this century turned this around, proclaiming the well-made artifact the equal of the work of art and, in all essential ways, indistinguishable from it. The difficulty may not be amenable to any final settlement. There is a common good desired of them both: We want our furnishings as well as our pictures to be beautiful. But their capabilities and purposes can also differ widely; and that needs to be accounted for before this search for understanding ends. Yet, for our start it will be helpful that the ground rules for creating a good product govern equally the object of utility and one existing solely for its beauty – the Applied as well as the Fine Arts. B. John Benson’s Course and the Twin Purposes of All Instruction Undergraduates at Rhode Island School of Design in the 1950s studied during one semester a subject called Philosophy of Design. The course was taught by a great man, John Howard Benson. It was beautifully organized, and ably introduced us to a domain of intellectual concern that few artists ever get to know. Also, it fulfilled better than most others the twin purposes of all instruction:

C. Ways of Delivering the Wrong Results When an otter lies upon its back and opens a mussel by breaking the casing with a stone, or a raptor rises to some height and drops its catch to shatter on the ground below, or again, an early hominid seized a rock to cleave with it the brain-case of his game, the deeds appear identical in their complexity of mental action. But they are most dissimilar in their cultural and, in the end, historic consequences. Man alone evolved to overcome, to an extent, the specific limits all other species failed to breach. These, however, remain the causes of inferior work at the hands of man, to the present day. They are:

D. The Worthwhile and Essential Callings of Man’s Life

E. The Causes of Things Made There are reasons, or causes, why Man-Made Things Exist

and of the materials to each other. Techniques are the union of the Material and Efficient Causes. Materials properly chosen for their purpose are shaped according to what the right tools and materials can suitably be made, and want, to do for a desired end. 4. Formal Cause: The solution of the problem and its final form are achieved in Stages. The Stages are reductions, that is, Abstractions derived from the problem posted by the patron. Stages constitute the successive images to which the materials must by shaped. [Other Causes than those cited as Antecedents of Results –from notes at end of essay:

F. Stages as Instrumental Intermediate Forms

knowledge, will, and skill, but also inventive sensibility, is brought to bear to set the correct milestones in their places as the Work Path gradually unfolds. It is here, when we must rely on our uncertain intuitions, that we cannot altogether escape our own uneasiness of mind. 3. The last of the abstractions that we call a Stage is the Final Form and conclusion of the worker’s effort. It represents perfection as a thing complete and thoroughly constructed. Perfection is here not an attribute divine, but must be rightly understood as a property of man-made things within their range of possibilities, that is, within the impediments or limits of the job. When the last possible duty is faithfully performed, perfection as achieved because we can do no more – the final chore and last detail. Comment:

Perhaps you can comment from work you have done in Arts, Crafts or other projects using Stages as Intermediate Forms . . . . |

A Blog containing longer text selections from essays by Johannes, on art, philosophy, religion and the humanities, written during the course of a lifetime. Artists are not art historians. People who write are not all learned scholars. This can lead to “repeat originality” on most rare occasions. When we briefly share a pathway of inquiry with others, we sometimes also must share the same results.

Categories

All

Archives |

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Writes |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed