|

In the early 1990s this was given first as a speech to a class at the Lancaster County Art Association, and in briefer form afterwards on a couple of other occasions. Some of the illustrations come from the text, others from references to physical works that Johannes brought with him, and one from live demonstration. (3rd of eleven sections) II The Transmission of Knowledge A. Dexterity Training Today objects of utility are products of industrial virtuosity and “know-how,” and the machines that shape them are the vastly powerful offspring of the classical tools designed for manual use. The computer may permit a parallel industrial development also in the Fine Arts toward which, at present, there is both skepticism and enthusiasm. We must admire the sheer technical magnificence that the computer has made so readily available. But the seeing eye is subtler than we easily observe and may find eventually something bleak and arid in endless repetitions of computer “fireworks.” It would be a sad result, if all the love and adulation lavished today on the computer, brought to us tomorrow a nostalgia movement for the second time around, because our prevailing culture of that day will be too sterile and too feeble to nurture our souls.

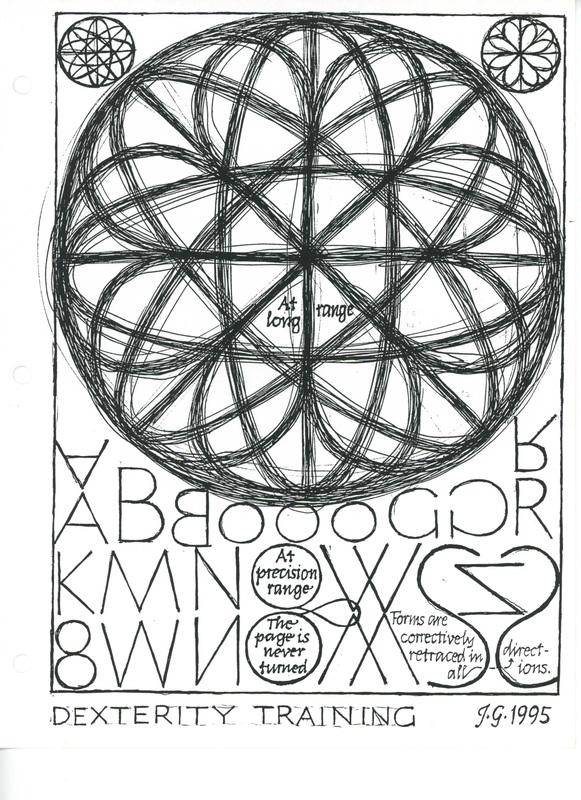

2. Skill Training in Calligraphy and Drawing: I have known only a single Drawing Course prescribing exercises, in the form of drills, for manual control. Instead, Calligraphy has generally taken up that task to much good purpose, so that, even in my drawing courses, I have included letter forms for dexterity instruction. Dexterity improves to varying degree with any art work we perform – but only over time, so that, in the present series of four speeches, I cannot help you to become more skillful. But I may attempt to add a little to what we understand. B. Intellect and Will Will, Intellect and Intuition are used as words so confidently that it is easy to be unaware how little we were ever taught about them. Though the will cannot determine what the knowledge of a subject is, this knowledge cannot constitute itself without the energy of the will.

2. The Will: Not all feelings are emotional. For we can receive them in happy timespans of fulfillment while emoting nothing.

us how frivolously one may employ both intellect and will. The emoting Will can enslave and put the Intellect to work for any cause. 3. Education: In youth our unattached emotional energy surges in every direction. And through education – not by the schools alone, but in the sense of an ancient wisdom out of Africa that it takes an entire village (a whole society) to raise a child – we must hope to reach that vast reservoir and powerful potential.

one of requirements – though we meet them badly – and not just personal bent and impulse. Eventually, self-expenditure can help youth to cherish the good products of their labor more than any ready pleasures falling unearned into their empty lives, and to cherish also in a little way themselves as people who have worked faithfully to learn to behave properly and labor thoroughly and well. And so the personality begins to grow into an enduring likeness of the way we live and work.

C. The Three Ways of Seeing as Three Ways of Learning The Three Ways of Seeing would be: Naturalistic Seeing – through Observation; Derivative Seeing – from Experience; and Original Seeing – as a Creative Vision. This last inclusion is owed to John Howard Benson’s course. When we call these three divisions the Three Ways of Learning, some of them may gain a little ground.

2. Derivative Learning is a discipline of Prudence, or Right Doing, as well as of Right Knowing, gained from our teachers rather than from Nature. It is the Learning transmitted through an education based on past experience, and its value is two-fold:

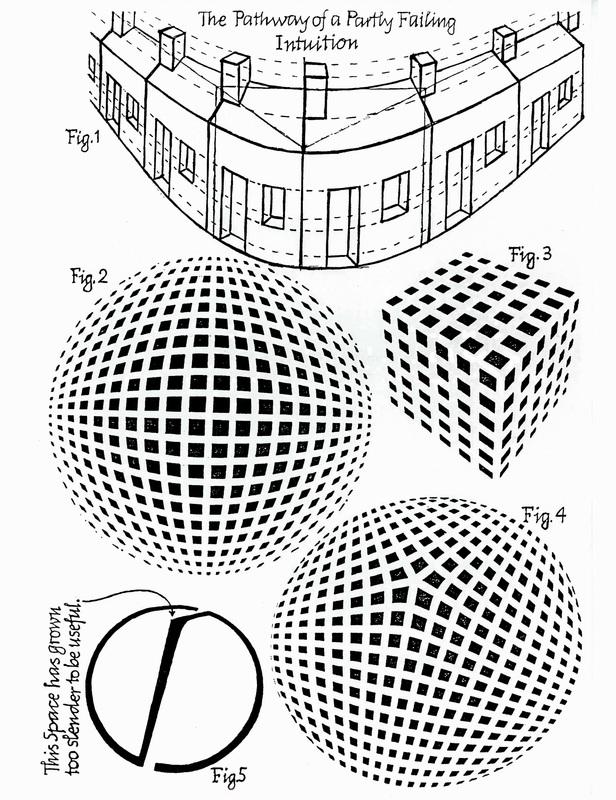

the most up-to-date, at the time of teaching, is confirmed. So, if he masters it and learns to work with it, the student cannot really fail. 3. Original Learning: To profit as abundantly as possible from listening to others, we must listen also to the voice of our personal understanding – that is, to ourselves. A self-created pattern of sensible, experimental forecasts must now provide the guidance to a deeper understanding and a more useful, nobler product. That achievement is the work of intuition that I must now describe in some detail. Useful intuition comes mostly to the well-prepared. D. The Pathway of a Partly Failing Intuition

2. An intuition is easily mistaken for a feeling, because the well-familiar information from which it is descended is taken much for granted and hence no longer paid attention – and also because hope, even anticipating joy, attend promising intuitive perceptions. An anticipation – no longer perceived against the background of its origins, and attended by strong feeling – will easily itself appear as a feeling. But we can no longer so mistake intuition if we keep in our sight the preparatory knowledge which brought the intuition within the range of our speculations.

3. Intuition is precognitive (foreknowing) in its character, and does its work by leading us to knowledge – that is, to full cognition. Given their rational foundation, its forecasts have to be of intellectual substance – not as a solid certainty – but as an intellectual probe. Thus I rely upon my intuitions all the time. For without its capabilities, there are no advances. But an intuition can only serve us well if we treat with skepticism every result it urges and then express our distrust by a thorough work of testing. This is truly most important – that you must distrust your intuitions in order to obtain from them all the benefit they have to give. 4. Were I to be your teacher, perhaps daily over many years, I could help you to improve your skill and show you how you might proceed, with prudent discipline, to achieve the results for which my teaching aims. But I could do no more – and it is a most uncertain game – than hope to stimulate your intuition. And you might not like me very much for trying. For Stimulus is Latin for a cattle-prod, and who could welcome the sort of treatment such a tool implies? Important intuitions must instead result always from lighting one’s own fires. But useful knowledge – as we have clearly seen – can provide the kindling spark. And I may share with you, perhaps, some useful knowledge even in these few short hours we can have together. Comment:

Have you ever encountered a course like The Philosophy of Design taught in the 1950s by John Howard Benson?

0 Comments

In the early 1990s this was given first as a speech to a class at the Lancaster County Art Association, and in briefer form afterwards on a couple of other occasions. Some of the illustrations come from the text, others from references to physical works that Johannes brought with him, and one from live demonstration. (2nd of eleven sections) G. Perfection, Compromise and Wear

H. The Integrity and Wholeness of a Perfect Thing The constraints of compromise and wear are difficulties which we may dismiss once we have managed them as well as circumstance allows. But we can center ourselves so narrowly on practical utility that we are scarcely able to endure and live with our functional creations. Unsightliness – through irritating or distracting and thereby weakening the user – impairs the function of an object. Moreover, artifacts are not just with us when they do their work, but also at their idle periods. Thus, among their varied functions, that of giving satisfaction to the viewer who beholds them has to be included. An artifact is made completely – that is, wholly finished and in that sense perfect – when visual excellence and utility are joined. When a man-made thing thus embodies an optimal reply to each of the user’s sensible requirements, it will bear wholly the character of all that it is made to be. It will be itself. That is, within the constraints of its own integrity, it will be perfection, in quite a similar sense that geometric shapes also can be perfect. A circle, for example, will be perfect within the limits of its own identity, because it is unsurpassable in its character of circularity. I. The Excellence of Art Visual excellence is an attribute of all good art toward one especial function, namely, that of being seen. It is essential in both the applied as well as fine arts, and consists at least of two requirements.

of grapes and prefer blonde girls to brunettes. Just proportionality gives to us the unimpeded visual coherence of a thing and hence its ready legibility. (This should be demonstrated live.) 2. Clarity: However, clarity is an intrinsic property of the work itself and therefore no more dependent upon who can look at it with understanding than is the legibility of writing to be judged by those who do not know their letters. For clarity inheres in the exactitude of the artist’s reconstruction of his purpose in visible material form. Clarity brings illumination into our minds and is there loved by our understanding. Clarity does not mean an expression is directly understood but only that it is amenable to comprehension. However, since we mostly want to understand any subject we consider, we love lucidity for granting us what we desire. J. The Common Foundation The Basic Designs – both two and three dimensional – are a line of learning aimed at Visual Literacy pursued by students in every field of art but thereafter put to different uses. All able expression of visual literacy is valuable and deserves a place in art. But the different art disciplines do not, on that account, produce interchangeable results. 1. Pictorial Limitation: I cannot put my pictures to work to pour coffee or bicycle myself downtown. But, equally, I cannot put the artifacts suitable for these two uses to the assignments that pictures may perform. 2. Pictorial Expression:

2. Pictorial Expression (cont’d)

2. Pictorial Expression (cont’d)

Pictorial interpretation of Literature, Fantasy and Life is beyond the reach of objects of utility, which are expressive chiefly of the use to which we put them, and closely limited therefore to an excellence of visual form and the material service desired by the patron, without profound interpretive intention. 3. Artifacts in Numbers: The potential of an artifact is thus exhausted only if we regard it by itself. A work of Architecture with various details – inside as well as out – and its assembly of artifacts for every sort of use, especially indoors, can, overall, be far more than the sum of all these parts. They can give an eloquent articulation of the owners’ habits, character and will. Whole human lives express themselves that way. The discipline of Archaeology, from just such clues, endeavors to reconstruct entire cultures. Thus, artifacts in numbers – coherently selected and arrayed, achieve an expressive range that eludes them singly. For this breadth of creativity, apparently, was Architecture named “Queen of all the Arts” by Michelangelo. Artifacts can be as powerfully and as far expressive as products of the Fine Arts. But while the latter are able to achieve this purpose singly, artifacts themselves cannot. Yet, of the many times when a judgment of what will be better and what worse cannot be evaded, in this case we may let the question rest and strive to design better the objects of utility as well as nobler works of art. It is important only to thoroughly understand what each is all about. K. Two Definitions of Art

2. Defining the Purpose of the Making: Visual Art is a language for engaging the participation – not of our sense of hearing, but of sight – for sharing, by an apt assembly of the visual parts of color, form, and line, the artist’s intention, with our open eyes and receptive minds, so that we shall be enriched and, in the end, fulfilled. Comment: You might describe an artifact which you own and love that is beautiful and expressive - a work of art in itself . . . We begin this series with the early essay which gives its name to this column - written in 1959. (Fourth of six sections) Power of Implication

The linkage, then, of one fully recognized fact to the identity of another is an exploitation of the relative powers contained in each. In so linking the implications of facts to one another, we achieve a highly mobile process that we know on the intellectual level as thinking. On this basis I must describe thinking as a moving from the acknowledgment of one identity to further assessments, prescribed and directed by the relative energy of the identity already recognized. Thus our thoughts insist on conceiving themselves, as soon as the location of our interest has determined the theme. Once before I have touched on this peculiar insistence of things made by man for taking their fate in their own hands and permitting us to see in our products not invention, but only discovery. Whatever we begin to validly conceive or make is contained already in its potential nature as part of the condition of worldly being, and is well able to direct us by its demands. Our most fruitful activity in thinking and making is bound to insight and recognition, not to a willful burst of egotism. Potential Meaning The potential being of all our concepts and works must, however, be recognized in its difference from an existence in perceivable reality. For the potential is not its realization in the actual until potentiality is turned to fulfill its implied assignment. In the potential, then, is the contributive power to be relatively involved that we find included in the identity of all things. These, from their own actuality, may be extended to seize the relative endowment of another equally real existence and enter a union with it. The resulting compound would possess the sovereignty of the actual and be endowed in its turn with ability to extend relative energy in the direction of a still further independent identity. Evidently the human being, too, is self-contained in a unit of meaning that, in the absoluteness of identity, possesses gifts of relative implication in the ability to recognize and conceive intellectually and to make physically. A number of disks, designed to rotate around their axes, and a box-like framework or structure each own the properties of their identity, including the potential relative functions of wheel and chassis. But the acknowledged identities, with their recognized relative implications, do not in themselves constitute a carriage. The powers of intelligent insight and physical making, contained in the identity of man, are extended as a contribution that renders the potential actual. Now in its own right this offers the relative powers that its new compound identity possesses to allow further speculation in the direction, for instance, of motorization and diverse transport services. Intellectual insight and the will and capacity for work based on that insight are the contribution which man is empowered to make to the contribution already offered by his environment. Wheels and chassis as a carriage are not a heap of accumulated junk. They are the whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, greater to the precise extent of human collaboration in terms of wisdom and work. The Human Potential for God Insight and thinking, as well as physical making, are among the relative abilities included in the essence of the human being. But so are faith and believing. If we accept the existence of God, we give recognition to an inexplicable presence, to a being whom we understand to surpass all comprehensible limits, whose content is “meaning in the infinite.” The capacity for rational thought is no avenue to God, unless its logic compels the insight that faith and believing are fitting for those to whom it is not given to know. Instead of the light to see, there is the will to believe and, because willing is an act of sovereignty, surrender in faith does not diminish the human stature. By approaching God as His identity and our inability to understand requires, namely in faith, we are not submitting to some sort of tyranny, but on the contrary, exercising the prerogative to give or withhold ourselves. As no gift is reduced or altered by the change of hands from giver to receiver, so the gift of ourselves to the majesty of God suffers no reduction in meaning. And its unique identity remains intact, for we must possess as property what we offer as a gift. In the act of faith we hold the strength to find function and purpose in the void. This emptiness would cancel all meaning beyond the limits of humanly possible knowledge if we were not fashioned to relate meaningfully to the inexplicable, by the will to believe where the insight to know is withheld. And so it appears that, by way of faith, we are committed, in a catechismic sense, to the doing of good and the surrender to God’s will. For we cannot, in all the essence of realism, ignore our gift to believe, where we meet cause to make use of it. We begin this series with the early essay which gives its name to this column - written in 1959. (Third of six sections) Creation and Creator

If I am to maintain my point of view regarding the autonomous character in the meaning of all things, then I am in consequence forced to acknowledge the personal separateness of human existence from the identity of God. The temptation may be great to toy with the sound of words, to say that the concept of creature and creation cannot be understood in any other way than in forever dependent relation to the Creator. These words, however, play a misleading game, and may move the more arrogant among us to state in addition that the Creator does not meaningfully exist, unless it be in relation to creature and creation. In this curious fashion God would be reduced to a level of being where He depended on our existence for meaning in His. I am undecided whether this would be a mere error or the beginning of blasphemy. It is my conviction that, when God completed all He has made, the navel cord between Him and us was severed, when we were given volition and choice – in effect – a self-contained identity. He has set us free, and correspondingly freed his own identity from ours. He is creator by the nature of His omnipotence – the authority to do all things – not because He has made a world and put us in it. Had He never made us, His creator identity would have suffered no reduction from the omission, as it received no increase from the act. To Relate Meaning The preoccupation with meaning in an absolute sense is in no way intended to diminish or deny the importance of the relative coexistence which we observe in the interaction of innumerable things. We are now, however, aware that each thing must contain its meaning within its own identity before it can relate meaningfully to another equally qualified. I should like to state that meaning in the absolute is the presupposed condition upon which meaning in the relative must rest. And, by the same token, it should be added that the relative is the vehicle by which absolutes relate their meaning to each other. So far this investigation has not yet revealed the very typical activity which is required if one thing is to involve itself relatively with another. To study the act which extends the meaning of one identity, and makes it available to the other, is the task to which I am now most urgently put. Despite an unchangeable character founded in identity, it does seem that, included within the integrity of each thing, there is a flexibility of potential functional activity. This participates in the overriding nature of its meaning and is able to extend that meaning of total oneness in many directions, and engage it in diverse forms of coexistence. Maybe it is of some value here – or at any rate, expedient – to resort to exemplification in order to demonstrate the act of relative functioning. Relations of “Four” Assuming any number, “4,” for instance, and giving recognition to its unshakeable character as a symbol of four exactly equal entities, we may yet consider a variety of arithmetical functions in which this value may be employed. Four can be divisor or multiplier, dividend or multiplicand, positive or negative. In this way it is varied in its relative function, but the “fourness” which identifies it is inviolable. Our knowledge of the fact “four,” however, remains incomplete if we do not recognize the relative powers that imply potential and are included in its absolute identity. “Four” owns these powers independently of whatever use we find to employ them from case to case. Therefore it is not truly possible to know an isolated fact. For, to be ignorant of the particular relative strengths included in each fact is to not know it all. Recognition of relative function allows us to examine the identity of a fact from as many sides as there are directions of potential impact upon other entities. Such close scrutiny of all facets reveals an entirety. It does not permit us to be misguided into the belief that a thing has changed identity merely because it relates its meaning in a different way to a different thing than habit is wont to perceive. Seeing from all sides is knowing all directions of potential relative extension to which an existence is empowered by virtue of being. Taking for granted, at the time, the relative powers held within the significance of each word, I was able to look upon the poem mentioned earlier as a self-sufficient unit of meaning and disown it in terms of principle, without either mention or speculation in regard to specific content. And indeed, its theme and subject matter, all-important on their own terms, have not in any way become more relevant now in this discussion. It is, however, essential to realize the complexity of every poem as a unit of meaning that comprises, as one entity, the interrelation of all single meanings that it integrates. Though I maintain that the integration of single facts is a sovereign identity, its meaning in all its oneness is of compound character. |

A Blog containing longer text selections from essays by Johannes, on art, philosophy, religion and the humanities, written during the course of a lifetime. Artists are not art historians. People who write are not all learned scholars. This can lead to “repeat originality” on most rare occasions. When we briefly share a pathway of inquiry with others, we sometimes also must share the same results.

Categories

All

Archives |

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Writes |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed