|

The FINAL week -- with summary conclusions for "What is a beautiful thing?" and "Why pursue beauty?" and the meaning of true fulfillment for our leisure time. F. The Definition – What is a Beautiful Thing? Just as a thing is interesting when it engages the participation of the intellect, so is beauty its ability to engage us through the senses which, in our present line of interest, is the sense of sight. If we have reached agreement on my live demonstrations, two things will have been made clear.

display. It is the ability to look at ourselves while looking at a thing. G. The Purpose – Why Do We Pursue It? If we ask what makes a beautiful thing desirable to have, we get invariably the reply: “It pleases.” So it often does, but decidedly not always:

Literature, of all the arts, uses the comprehending intellect as if it were one of our senses. For, the reading eye alone would see page by weary page a single basic pattern endlessly repeated. But form and composition speak at first to the brain itself as if it were purely an organ of reception – a retina and eardrum of the mind. What unfolds in all my three examples are terrifying tragedies. To be gratified or well-pleased with them would be indeed satanic pleasure – a diabolical amusement. But, even while the heart is saddened, these works can so utterly engage all our mind and feeling that no foreign desires are able to intrude, and no distractions tarnish, the experience. Thus we learn through them a perfection of fulfillment.

The Purpose – Why Pursue Beauty? (cont’d)

2. But to love and learn about the Arts we have to measure up to them. We have the right to assess any work against the artist’s claim – his promise, if you will – that he is showing it to us because it will be a first rate thing to see. Yet, as viewers we must have good will, seek to un-learn our prejudices, and shed the common failing of ill-tempered and pedantic carping. For these will surely shut the doors on art. Besides good will, and by the instrument and reason of good will, we have to learn to open our eyes and to develop a clear mind, to be – to the best of our ability – a Noble Viewer for the artist’s work.

The Sciences – and here we must include Philosophy among them – are also fulfilling and enriching. But the Fine Arts and the Sciences cannot take one another’s place.

The Arts, however, can transport us to another world where our daily troubles matter little, and where we are refreshed as if we went on a vacation.

but because it simultaneously enriches and fulfills and restores our weary spirit, in a compact – one almost wants to say “efficient” – form that nothing else can quite achieve. 4. Finally, works of art can give to us this true refreshment and unburdening from our common cares in ways no artifact can altogether equal. H. A Change of Pace Rather than Escape

weaken him in the execution of his tasks. We assume therefore that ugly surroundings damage man’s ability to perform his proper work in life. Yet the unimaginable hell of a world entirely devoid of art – despite our inner city slums – still remains, I hope, mostly outside of human ken. But we are not prevented by our dependency on art from also wanting the truth of science and the reality in which it operates. We are not put to flight by reality. 2. The escapes of mindless thrills and pleasures cannot provide this change of pace we need for our restoration. For, largely disengaged intellects and sensibilities mean a relaxation of no pace at all.The mind-deadening effects of numerous television offerings – that is, the resulting sluggishness toward mental action – show that downward self-fulfillments as a class, far from giving us refreshment, put us beyond the reach of any restoration. 3. But the Arts demand of us a diligence and an attention that will bring us true enrichment instead of a mere land of dreams. For they alter solely the use we make of our faculties, and thus sharpen them into alertness, instead of rendering them numb. Leisure time is time which truly belongs to ourselves, and we should get from it all the benefits we may. The Arts are more suitable than almost any other instrument for gaining such a purpose. Johannes H. von Gumppenberg Lancaster, PA October 24, 1995

0 Comments

In the early 1990s this was given first as a speech to a class at the Lancaster County Art Association, and in briefer form afterwards on a couple of other occasions. Some of the illustrations come from the text, others from references to physical works that Johannes brought with him, and one from live demonstration. (3rd of eleven sections) II The Transmission of Knowledge A. Dexterity Training Today objects of utility are products of industrial virtuosity and “know-how,” and the machines that shape them are the vastly powerful offspring of the classical tools designed for manual use. The computer may permit a parallel industrial development also in the Fine Arts toward which, at present, there is both skepticism and enthusiasm. We must admire the sheer technical magnificence that the computer has made so readily available. But the seeing eye is subtler than we easily observe and may find eventually something bleak and arid in endless repetitions of computer “fireworks.” It would be a sad result, if all the love and adulation lavished today on the computer, brought to us tomorrow a nostalgia movement for the second time around, because our prevailing culture of that day will be too sterile and too feeble to nurture our souls.

2. Skill Training in Calligraphy and Drawing: I have known only a single Drawing Course prescribing exercises, in the form of drills, for manual control. Instead, Calligraphy has generally taken up that task to much good purpose, so that, even in my drawing courses, I have included letter forms for dexterity instruction. Dexterity improves to varying degree with any art work we perform – but only over time, so that, in the present series of four speeches, I cannot help you to become more skillful. But I may attempt to add a little to what we understand. B. Intellect and Will Will, Intellect and Intuition are used as words so confidently that it is easy to be unaware how little we were ever taught about them. Though the will cannot determine what the knowledge of a subject is, this knowledge cannot constitute itself without the energy of the will.

2. The Will: Not all feelings are emotional. For we can receive them in happy timespans of fulfillment while emoting nothing.

us how frivolously one may employ both intellect and will. The emoting Will can enslave and put the Intellect to work for any cause. 3. Education: In youth our unattached emotional energy surges in every direction. And through education – not by the schools alone, but in the sense of an ancient wisdom out of Africa that it takes an entire village (a whole society) to raise a child – we must hope to reach that vast reservoir and powerful potential.

one of requirements – though we meet them badly – and not just personal bent and impulse. Eventually, self-expenditure can help youth to cherish the good products of their labor more than any ready pleasures falling unearned into their empty lives, and to cherish also in a little way themselves as people who have worked faithfully to learn to behave properly and labor thoroughly and well. And so the personality begins to grow into an enduring likeness of the way we live and work.

C. The Three Ways of Seeing as Three Ways of Learning The Three Ways of Seeing would be: Naturalistic Seeing – through Observation; Derivative Seeing – from Experience; and Original Seeing – as a Creative Vision. This last inclusion is owed to John Howard Benson’s course. When we call these three divisions the Three Ways of Learning, some of them may gain a little ground.

2. Derivative Learning is a discipline of Prudence, or Right Doing, as well as of Right Knowing, gained from our teachers rather than from Nature. It is the Learning transmitted through an education based on past experience, and its value is two-fold:

the most up-to-date, at the time of teaching, is confirmed. So, if he masters it and learns to work with it, the student cannot really fail. 3. Original Learning: To profit as abundantly as possible from listening to others, we must listen also to the voice of our personal understanding – that is, to ourselves. A self-created pattern of sensible, experimental forecasts must now provide the guidance to a deeper understanding and a more useful, nobler product. That achievement is the work of intuition that I must now describe in some detail. Useful intuition comes mostly to the well-prepared. D. The Pathway of a Partly Failing Intuition

2. An intuition is easily mistaken for a feeling, because the well-familiar information from which it is descended is taken much for granted and hence no longer paid attention – and also because hope, even anticipating joy, attend promising intuitive perceptions. An anticipation – no longer perceived against the background of its origins, and attended by strong feeling – will easily itself appear as a feeling. But we can no longer so mistake intuition if we keep in our sight the preparatory knowledge which brought the intuition within the range of our speculations.

3. Intuition is precognitive (foreknowing) in its character, and does its work by leading us to knowledge – that is, to full cognition. Given their rational foundation, its forecasts have to be of intellectual substance – not as a solid certainty – but as an intellectual probe. Thus I rely upon my intuitions all the time. For without its capabilities, there are no advances. But an intuition can only serve us well if we treat with skepticism every result it urges and then express our distrust by a thorough work of testing. This is truly most important – that you must distrust your intuitions in order to obtain from them all the benefit they have to give. 4. Were I to be your teacher, perhaps daily over many years, I could help you to improve your skill and show you how you might proceed, with prudent discipline, to achieve the results for which my teaching aims. But I could do no more – and it is a most uncertain game – than hope to stimulate your intuition. And you might not like me very much for trying. For Stimulus is Latin for a cattle-prod, and who could welcome the sort of treatment such a tool implies? Important intuitions must instead result always from lighting one’s own fires. But useful knowledge – as we have clearly seen – can provide the kindling spark. And I may share with you, perhaps, some useful knowledge even in these few short hours we can have together. Comment:

Have you ever encountered a course like The Philosophy of Design taught in the 1950s by John Howard Benson? In the early 1990s this was given first as a speech to a class at the Lancaster County Art Association, and in briefer form afterwards on a couple of other occasions. Some of the illustrations come from the text, others from references to physical works that Johannes brought with him, and one from live demonstration. (2nd of eleven sections) G. Perfection, Compromise and Wear

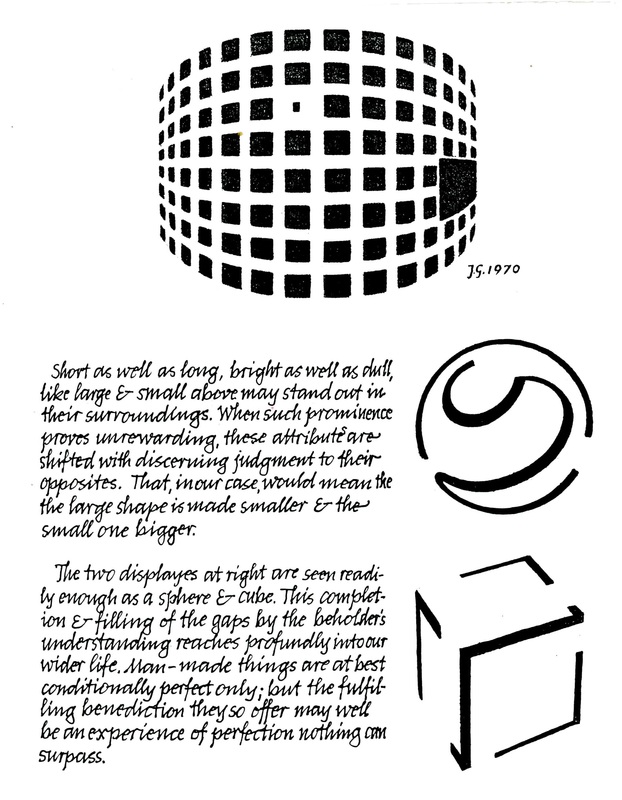

H. The Integrity and Wholeness of a Perfect Thing The constraints of compromise and wear are difficulties which we may dismiss once we have managed them as well as circumstance allows. But we can center ourselves so narrowly on practical utility that we are scarcely able to endure and live with our functional creations. Unsightliness – through irritating or distracting and thereby weakening the user – impairs the function of an object. Moreover, artifacts are not just with us when they do their work, but also at their idle periods. Thus, among their varied functions, that of giving satisfaction to the viewer who beholds them has to be included. An artifact is made completely – that is, wholly finished and in that sense perfect – when visual excellence and utility are joined. When a man-made thing thus embodies an optimal reply to each of the user’s sensible requirements, it will bear wholly the character of all that it is made to be. It will be itself. That is, within the constraints of its own integrity, it will be perfection, in quite a similar sense that geometric shapes also can be perfect. A circle, for example, will be perfect within the limits of its own identity, because it is unsurpassable in its character of circularity. I. The Excellence of Art Visual excellence is an attribute of all good art toward one especial function, namely, that of being seen. It is essential in both the applied as well as fine arts, and consists at least of two requirements.

of grapes and prefer blonde girls to brunettes. Just proportionality gives to us the unimpeded visual coherence of a thing and hence its ready legibility. (This should be demonstrated live.) 2. Clarity: However, clarity is an intrinsic property of the work itself and therefore no more dependent upon who can look at it with understanding than is the legibility of writing to be judged by those who do not know their letters. For clarity inheres in the exactitude of the artist’s reconstruction of his purpose in visible material form. Clarity brings illumination into our minds and is there loved by our understanding. Clarity does not mean an expression is directly understood but only that it is amenable to comprehension. However, since we mostly want to understand any subject we consider, we love lucidity for granting us what we desire. J. The Common Foundation The Basic Designs – both two and three dimensional – are a line of learning aimed at Visual Literacy pursued by students in every field of art but thereafter put to different uses. All able expression of visual literacy is valuable and deserves a place in art. But the different art disciplines do not, on that account, produce interchangeable results. 1. Pictorial Limitation: I cannot put my pictures to work to pour coffee or bicycle myself downtown. But, equally, I cannot put the artifacts suitable for these two uses to the assignments that pictures may perform. 2. Pictorial Expression:

2. Pictorial Expression (cont’d)

2. Pictorial Expression (cont’d)

Pictorial interpretation of Literature, Fantasy and Life is beyond the reach of objects of utility, which are expressive chiefly of the use to which we put them, and closely limited therefore to an excellence of visual form and the material service desired by the patron, without profound interpretive intention. 3. Artifacts in Numbers: The potential of an artifact is thus exhausted only if we regard it by itself. A work of Architecture with various details – inside as well as out – and its assembly of artifacts for every sort of use, especially indoors, can, overall, be far more than the sum of all these parts. They can give an eloquent articulation of the owners’ habits, character and will. Whole human lives express themselves that way. The discipline of Archaeology, from just such clues, endeavors to reconstruct entire cultures. Thus, artifacts in numbers – coherently selected and arrayed, achieve an expressive range that eludes them singly. For this breadth of creativity, apparently, was Architecture named “Queen of all the Arts” by Michelangelo. Artifacts can be as powerfully and as far expressive as products of the Fine Arts. But while the latter are able to achieve this purpose singly, artifacts themselves cannot. Yet, of the many times when a judgment of what will be better and what worse cannot be evaded, in this case we may let the question rest and strive to design better the objects of utility as well as nobler works of art. It is important only to thoroughly understand what each is all about. K. Two Definitions of Art

2. Defining the Purpose of the Making: Visual Art is a language for engaging the participation – not of our sense of hearing, but of sight – for sharing, by an apt assembly of the visual parts of color, form, and line, the artist’s intention, with our open eyes and receptive minds, so that we shall be enriched and, in the end, fulfilled. Comment: You might describe an artifact which you own and love that is beautiful and expressive - a work of art in itself . . . In the early 1990s this was given first as a speech to a class at the Lancaster County Art Association, and in briefer form afterwards on a couple of other occasions. Some of the illustrations come from the text, others from references to physical works that Johannes brought with him, and one from live demonstration. (FIRST of eleven sections) I The Artifact and the Art Object A. Rules for Right Making in Utility and Art In past times distinctions were drawn between products of the Fine Arts and humble Objects of Utility, adding to the latter ever the inferior rank. Much thinking in this century turned this around, proclaiming the well-made artifact the equal of the work of art and, in all essential ways, indistinguishable from it. The difficulty may not be amenable to any final settlement. There is a common good desired of them both: We want our furnishings as well as our pictures to be beautiful. But their capabilities and purposes can also differ widely; and that needs to be accounted for before this search for understanding ends. Yet, for our start it will be helpful that the ground rules for creating a good product govern equally the object of utility and one existing solely for its beauty – the Applied as well as the Fine Arts. B. John Benson’s Course and the Twin Purposes of All Instruction Undergraduates at Rhode Island School of Design in the 1950s studied during one semester a subject called Philosophy of Design. The course was taught by a great man, John Howard Benson. It was beautifully organized, and ably introduced us to a domain of intellectual concern that few artists ever get to know. Also, it fulfilled better than most others the twin purposes of all instruction:

C. Ways of Delivering the Wrong Results When an otter lies upon its back and opens a mussel by breaking the casing with a stone, or a raptor rises to some height and drops its catch to shatter on the ground below, or again, an early hominid seized a rock to cleave with it the brain-case of his game, the deeds appear identical in their complexity of mental action. But they are most dissimilar in their cultural and, in the end, historic consequences. Man alone evolved to overcome, to an extent, the specific limits all other species failed to breach. These, however, remain the causes of inferior work at the hands of man, to the present day. They are:

D. The Worthwhile and Essential Callings of Man’s Life

E. The Causes of Things Made There are reasons, or causes, why Man-Made Things Exist

and of the materials to each other. Techniques are the union of the Material and Efficient Causes. Materials properly chosen for their purpose are shaped according to what the right tools and materials can suitably be made, and want, to do for a desired end. 4. Formal Cause: The solution of the problem and its final form are achieved in Stages. The Stages are reductions, that is, Abstractions derived from the problem posted by the patron. Stages constitute the successive images to which the materials must by shaped. [Other Causes than those cited as Antecedents of Results –from notes at end of essay:

F. Stages as Instrumental Intermediate Forms

knowledge, will, and skill, but also inventive sensibility, is brought to bear to set the correct milestones in their places as the Work Path gradually unfolds. It is here, when we must rely on our uncertain intuitions, that we cannot altogether escape our own uneasiness of mind. 3. The last of the abstractions that we call a Stage is the Final Form and conclusion of the worker’s effort. It represents perfection as a thing complete and thoroughly constructed. Perfection is here not an attribute divine, but must be rightly understood as a property of man-made things within their range of possibilities, that is, within the impediments or limits of the job. When the last possible duty is faithfully performed, perfection as achieved because we can do no more – the final chore and last detail. Comment:

Perhaps you can comment from work you have done in Arts, Crafts or other projects using Stages as Intermediate Forms . . . . We begin this series with the early essay which gives its name to this column - written in 1959. (Fourth of six sections) Power of Implication

The linkage, then, of one fully recognized fact to the identity of another is an exploitation of the relative powers contained in each. In so linking the implications of facts to one another, we achieve a highly mobile process that we know on the intellectual level as thinking. On this basis I must describe thinking as a moving from the acknowledgment of one identity to further assessments, prescribed and directed by the relative energy of the identity already recognized. Thus our thoughts insist on conceiving themselves, as soon as the location of our interest has determined the theme. Once before I have touched on this peculiar insistence of things made by man for taking their fate in their own hands and permitting us to see in our products not invention, but only discovery. Whatever we begin to validly conceive or make is contained already in its potential nature as part of the condition of worldly being, and is well able to direct us by its demands. Our most fruitful activity in thinking and making is bound to insight and recognition, not to a willful burst of egotism. Potential Meaning The potential being of all our concepts and works must, however, be recognized in its difference from an existence in perceivable reality. For the potential is not its realization in the actual until potentiality is turned to fulfill its implied assignment. In the potential, then, is the contributive power to be relatively involved that we find included in the identity of all things. These, from their own actuality, may be extended to seize the relative endowment of another equally real existence and enter a union with it. The resulting compound would possess the sovereignty of the actual and be endowed in its turn with ability to extend relative energy in the direction of a still further independent identity. Evidently the human being, too, is self-contained in a unit of meaning that, in the absoluteness of identity, possesses gifts of relative implication in the ability to recognize and conceive intellectually and to make physically. A number of disks, designed to rotate around their axes, and a box-like framework or structure each own the properties of their identity, including the potential relative functions of wheel and chassis. But the acknowledged identities, with their recognized relative implications, do not in themselves constitute a carriage. The powers of intelligent insight and physical making, contained in the identity of man, are extended as a contribution that renders the potential actual. Now in its own right this offers the relative powers that its new compound identity possesses to allow further speculation in the direction, for instance, of motorization and diverse transport services. Intellectual insight and the will and capacity for work based on that insight are the contribution which man is empowered to make to the contribution already offered by his environment. Wheels and chassis as a carriage are not a heap of accumulated junk. They are the whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, greater to the precise extent of human collaboration in terms of wisdom and work. The Human Potential for God Insight and thinking, as well as physical making, are among the relative abilities included in the essence of the human being. But so are faith and believing. If we accept the existence of God, we give recognition to an inexplicable presence, to a being whom we understand to surpass all comprehensible limits, whose content is “meaning in the infinite.” The capacity for rational thought is no avenue to God, unless its logic compels the insight that faith and believing are fitting for those to whom it is not given to know. Instead of the light to see, there is the will to believe and, because willing is an act of sovereignty, surrender in faith does not diminish the human stature. By approaching God as His identity and our inability to understand requires, namely in faith, we are not submitting to some sort of tyranny, but on the contrary, exercising the prerogative to give or withhold ourselves. As no gift is reduced or altered by the change of hands from giver to receiver, so the gift of ourselves to the majesty of God suffers no reduction in meaning. And its unique identity remains intact, for we must possess as property what we offer as a gift. In the act of faith we hold the strength to find function and purpose in the void. This emptiness would cancel all meaning beyond the limits of humanly possible knowledge if we were not fashioned to relate meaningfully to the inexplicable, by the will to believe where the insight to know is withheld. And so it appears that, by way of faith, we are committed, in a catechismic sense, to the doing of good and the surrender to God’s will. For we cannot, in all the essence of realism, ignore our gift to believe, where we meet cause to make use of it. We begin this series with the early essay which gives its name to this column - written in 1959. (Third of six sections) Creation and Creator

If I am to maintain my point of view regarding the autonomous character in the meaning of all things, then I am in consequence forced to acknowledge the personal separateness of human existence from the identity of God. The temptation may be great to toy with the sound of words, to say that the concept of creature and creation cannot be understood in any other way than in forever dependent relation to the Creator. These words, however, play a misleading game, and may move the more arrogant among us to state in addition that the Creator does not meaningfully exist, unless it be in relation to creature and creation. In this curious fashion God would be reduced to a level of being where He depended on our existence for meaning in His. I am undecided whether this would be a mere error or the beginning of blasphemy. It is my conviction that, when God completed all He has made, the navel cord between Him and us was severed, when we were given volition and choice – in effect – a self-contained identity. He has set us free, and correspondingly freed his own identity from ours. He is creator by the nature of His omnipotence – the authority to do all things – not because He has made a world and put us in it. Had He never made us, His creator identity would have suffered no reduction from the omission, as it received no increase from the act. To Relate Meaning The preoccupation with meaning in an absolute sense is in no way intended to diminish or deny the importance of the relative coexistence which we observe in the interaction of innumerable things. We are now, however, aware that each thing must contain its meaning within its own identity before it can relate meaningfully to another equally qualified. I should like to state that meaning in the absolute is the presupposed condition upon which meaning in the relative must rest. And, by the same token, it should be added that the relative is the vehicle by which absolutes relate their meaning to each other. So far this investigation has not yet revealed the very typical activity which is required if one thing is to involve itself relatively with another. To study the act which extends the meaning of one identity, and makes it available to the other, is the task to which I am now most urgently put. Despite an unchangeable character founded in identity, it does seem that, included within the integrity of each thing, there is a flexibility of potential functional activity. This participates in the overriding nature of its meaning and is able to extend that meaning of total oneness in many directions, and engage it in diverse forms of coexistence. Maybe it is of some value here – or at any rate, expedient – to resort to exemplification in order to demonstrate the act of relative functioning. Relations of “Four” Assuming any number, “4,” for instance, and giving recognition to its unshakeable character as a symbol of four exactly equal entities, we may yet consider a variety of arithmetical functions in which this value may be employed. Four can be divisor or multiplier, dividend or multiplicand, positive or negative. In this way it is varied in its relative function, but the “fourness” which identifies it is inviolable. Our knowledge of the fact “four,” however, remains incomplete if we do not recognize the relative powers that imply potential and are included in its absolute identity. “Four” owns these powers independently of whatever use we find to employ them from case to case. Therefore it is not truly possible to know an isolated fact. For, to be ignorant of the particular relative strengths included in each fact is to not know it all. Recognition of relative function allows us to examine the identity of a fact from as many sides as there are directions of potential impact upon other entities. Such close scrutiny of all facets reveals an entirety. It does not permit us to be misguided into the belief that a thing has changed identity merely because it relates its meaning in a different way to a different thing than habit is wont to perceive. Seeing from all sides is knowing all directions of potential relative extension to which an existence is empowered by virtue of being. Taking for granted, at the time, the relative powers held within the significance of each word, I was able to look upon the poem mentioned earlier as a self-sufficient unit of meaning and disown it in terms of principle, without either mention or speculation in regard to specific content. And indeed, its theme and subject matter, all-important on their own terms, have not in any way become more relevant now in this discussion. It is, however, essential to realize the complexity of every poem as a unit of meaning that comprises, as one entity, the interrelation of all single meanings that it integrates. Though I maintain that the integration of single facts is a sovereign identity, its meaning in all its oneness is of compound character. We begin this series with the early essay which gives its name to this column - written in 1959. (Second of six sections) An Epitome of Meaning

Human creativity, in all its man-made diversity, is perhaps more precisely qualified to provide insight into the nature of meaning than any object or condition which exists in a final, complete, and irrevocable state. For, what men think or make grows from shapeless nonexistence and vague notions to develop an integrity exclusively its own, by which it ripens into meaning. This meaning is the property of the thing so made and, if through the years it be wholly forgotten and engage in no relative activity, then the forgetting characterizes those who forget, but the integrity of a thing richly conceived and well-made is inviolate and therefore meaningful in itself. And so, to make myself more adequately clear, I am offering the invention of the following narrative. A lone traveler on a mule is riding slowly over a gray, barren land. Dusk is approaching and the jackass is weary, tottering ahead step by tortured step. As the two reach a muddy waterhole fringed with grass and clusters of sparse shrubs, the rider dismounts, his hand grips the bridle, and together they approach the edge of the pool. Man and animal drink side by side from the lukewarm and bitter water. Then the man unsaddles his mule and leaves it to graze. After gathering small pieces of dead wood, he lights a fire and cooks his indifferent meal. He eats slowly and, when the food is gone, he broods, buried in the thoughts of his mind. Stirred by something in his meditation, he takes a stubby pencil and a little paper from his saddlebag and, in the uncertain light of his low fire, begins to write. At one time he methodically whittles the point of his pencil, and at frequent intervals he crosses out what he has written and begins again. In the end, when he has crossed and rewritten for the last time, he turns to his animal and says, “Listen, Jackass, listen to what your master has written!” So, he reads his poem to an audience of none and a mule – a poem that is a small treasure of truth and humor, five or six lines wonderfully made. The man is sleepy now and the fire barely glowing, so he unfolds a blanket, wraps himself in it, and falls asleep. At sunrise he will wash, and boil his coffee, and ride away. Poem, poet, and jackass – nobody knowing what may become of them – will pass from sight. My little story may serve to illuminate the theme of absolute meaning by its particular insistence on isolating the integrity of the poem from all opportunity to communicate its content. I maintain that it was a meaningful poem nevertheless, a poem in a very complete and entire sense. For it was thoroughly and well done – all done – hence, all poem. And its identity and meaning rested in the strength it contained, not in the knowledge that a select group of people might have had of its existence, if it had been issued by a publishing house. Also, no significance may be attributed to the poem for another wrong reason, namely, that it must have related meaningfully to its author, as a kind of reciprocal gift in return for the love he so generously lavished in its making. We are bound by reality to accept the insight that, upon completion of a work, its dependence on the maker has also ended. Its existence is sovereign and can survive its author without reduction in meaning. Additionally, we must conclude that, for all the individuals who may know a given work, there must be a host of others who are entirely uninformed about its very existence. Thus, if we refuse to accept meaning in a definitive sense, we arrive at the nonsensical speculation whether the work has been rendered meaningful because of those, the author included, who know about it, or meaningless because of the others who do not. Moreover, meaningless work of poor quality in all fields is abundantly produced and displayed. Who could think in earnest that it has become meaningful because it has been made accessible to the public? So our lone traveler’s poem achieved meaning because it had been written, as the identity of its condition as a poem of whatever kind demanded to be written. A work, once its nature and intent are determined, requires, by dint of its emerging identity, treatment fitted to its own character, thereby in a sense insisting on making itself, as precisely and thoroughly as at all possible, so that nothing may either be taken from it or added. In this manner we are assured that the poem became in essence all of what it was and nothing that was not included in the particular nature and character to which it was committed. |

A Blog containing longer text selections from essays by Johannes, on art, philosophy, religion and the humanities, written during the course of a lifetime. Artists are not art historians. People who write are not all learned scholars. This can lead to “repeat originality” on most rare occasions. When we briefly share a pathway of inquiry with others, we sometimes also must share the same results.

Categories

All

Archives |

| von Gumppenberg | Johannes Writes |

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed